- 0

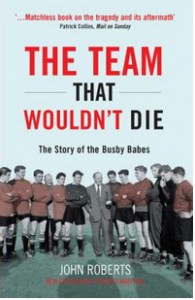

JOHN ROBERTS wrote for the Daily Express, The Guardian, the Daily Mail and The Independent, where he was the tennis correspondent for 20 years. He collaborated with Bill Shankly on the Liverpool manager’s autobiography, ghosted Kevin Keegan’s first book, and has written books on George Best, Manchester United’s Busby Babes (The Team That Wouldn’t Die) and Everton (The Official Centenary History).

As Matthew Engel once wrote in the British Journalism Review: “I suspect posh-paper sports writing changed forever the day John Roberts left the Daily Express to join The Guardian in the late 1970s, was handed a piece of routine agency copy and picked up a telephone to start asking questions.”

.

.

By John Roberts

25 April 2011

Aside from the silliness of showing the centre-half Mark Jones with a pipe in his mouth about to run on to the pitch with rest of the Busby Babes team, the BBC2 drama about the Munich air disaster, “United” (first aired last night) was guilty of errors of omission.

There was no mention of United’s secretary Walter Crickmer, who died as a result of the crash on 6 February 1958 along with Jones and seven team-mates among 23 casualties.

There was scant attention paid to Bill Foulkes, who would go on to captain a makeshift United team in the 1958 FA Cup Final and play his part in the club’s recovery leading to European Cup triumph 10 years later. There was no word either of the eight journalists who perished, including the former England goalkeeper, Frank Swift.

Perhaps most glaringly, where was James Thain, the captain in charge of the ill-fated Elizabethan aircraft who went ahead with a fatal third attempt at take-off ?

In 1974, when researching my book about the Babes, The Team That Wouldn’t Die, I contacted Captain Thain to arrange an interview. Initially he expressed reluctance to revive the subject, but relented, saying: “Bring a bottle of scotch.” When I arrived on his doorstep at Hayley Green Farm in Berkshire with a bottle, he said he was only joking about the whisky.

The captain, who emphatically did not accept blame for the crash, in which his co-pilot Captain Kenneth Rayment suffered fatal injuries, related the horror of the disaster, metaphorically placing me in his seat in the cockpit of the Elizabethan and taking me down the Munich runway three times.

There had been no reason to switch on a light as we began talking, and we became so engrossed that the room was almost in darkness before Thain finished reliving the crash and the ordeal of the fight to clear his name.

Prior to publication of the first edition of the book in 1975, and after reading a manuscript copy of the chapters in which he was involved, Thain wrote to me saying he had understood he was giving me background information and did not expect to be quoted directly. Never the less, he not only allowed his words to stand but also corrected any technical errors.

The disaster happened the day before Thain’s 37th birthday. He never flew again. He was 47 when finally cleared of blame for the crash in June 1969 after four inquiries, two German, two British.

The first inquiry, in West Germany, decided that the crash was caused by ice on the wings of the aircraft, which resulted in Thain being blamed because that was his responsibility. Thain was dissatisfied with the way this inquiry was conducted and disagreed with its findings. He believed the crash was caused by slush on the runway and fought on until this was finally accepted.

He told me that after the first inquiry British European Airways sent him an invoice for the cost of his airline cap, which had been lost in the wreckage.

On Christmas morning 1960 Thain was notified of his dismissal from British European Airways for a breach of their regulations in that he had changed seats with his first officer, Captain Kenneth Rayment. Rayment flew the aircraft from Belgrade from the left-hand seat. Thain occupied the right-hand seat.

It was permissable for the captain to allow his first officer to fly the aircraft provided the first officer was fully qualified. The first officer could act as “pilot in charge” and fly the plane while the captain took the role of co-pilot, but the captain remains in command.

However, BEA forbade the captain and first officer to change seats, insisting that the captain remain in the left-hand seat. Thain, acting as co-pilot from the left-hand seat, said he found it more difficult to monitor the instruments because they were not duplicated in front of him.

Thain and Rayment were friends as well as colleagues and Rayment, who had recently recovered from a hernia operation, was keen to fly again. “When I arrived to collect the charter plane, Ken was there” Thain recalled. “I said, ‘Right, I’ll take her to Belgrade and you can bring her back’. I must emphasise that we were both qualified pilots and both captains, in fact Ken had more flying time in Elizabethans than I had.

“BEA introduced the regulation about the seats after an incident involving a Dakota some time earlier. They insisted that the pilot in command should always sit in the left-hand seat, the seat to which he was accustomed. As a captain, Ken Rayment was accustomed to the left-hand seat.”

In the twilight at Hayley Green Farm in 1974, Thain recounted the final moments of that third trip down the runway:

“…Suddenly Ken shouted, ‘Christ! We won’t make it!’ Until then I had been looking at the instruments. When Ken shouted I looked up and could see a lot of snow and a house and a tree right in the path of the aircraft.

“I took my left hand from behind the throttle levers and banged them, but they were fully forward. I think Ken was pulling the control column back. He asked for the undercarriage to be lifted and I selected ‘up’.

“Then I put my hands out in front of me and gripped the ledge and peered over the edge. It seemed that we were turning to starboard and I was convinced we could not get between the house and the tree. I put my head down and waited for the impact of the crash.

“The aircraft went through a fence and crossed a road and the port wing hit the house. The wing and part of the tail were torn off and the house caught fire.

“As the aircraft spun, a tree just farther on than the house came through the port side of the flight deck where Ken was sitting. The starboard side of the fuselage hit a wooden hut, where there was a truck filled with tyres and fuel. This exploded.

“We were spinning and then the aircraft stopped. There was a hellish noise. And then complete silence.”

.

The Team That Wouldn’t Die is published in paperback by Aurum Press (£8.99)

The Team That Wouldn’t Die is published in paperback by Aurum Press (£8.99)

.