By Nick Harris

SJA Internet Sports Writer of the Year

25 March 2012

THERE were five sportsmen on board the Titanic when it sank on 15 April 1912, although their stories are unlikely to be given much if any attention during the eponymous ITV drama series which starts this weekend and will air in 80 countries in the coming weeks.

Two of them were Welsh boxers, Dai Bowen and Leslie Williams. They were travelling together in third class and both perished on that bitter Atlantic night as the band played on.

A third Briton, Charles Williams, was also on the doomed White Star liner. He was the world champion squash player at the time, en route to New York to defend his title. He survived, although he had to cancel his match.

And then there were two American tennis players, both stars at Wimbledon and other Grand Slam arenas in their time. They too survived.

Dick Williams, aka Richard Norris Williams, was aged 21 when the ship went down, and went on to win the US Open singles title twice, as well as various Grand Slam doubles titles and an Olympic gold medal.

Williams was actually born in Geneva, so was a Swiss-born multi-Slam champion decades before anyone had ever heard of a bloke called Federer.

His compatriot Titanic survivor was Karl Behr, 26, who had been a Wimbledon doubles runner-up in 1907 and later won the Davis Cup with the USA.

Williams and Behr had never met before the week that the Titanic sank but would go on to become friends, and sporting rivals, even meeting in the quarter-finals of the US Open two years after the Titanic disaster.

One day you might even see this depicted in a film. There’s already a book about it. A contentious one. But we’ll come back to that in a few moments.

Both the boxers originated from the Rhondda Valley in Wales, with Bowen living in Treherbert, and Williams in Tonypandy.

Both were listed as ‘pugilist’ on the passenger list and both were heading west to fulfill contracts for a series of prize fights when they lost their lives.

Bowen was 26, and the Welsh lightweight champion. He and his wife lived with Bowen’s widowed mother. In a letter written a few days before he died, Bowen wrote to his mum: ‘This is a lovely boat, she is very near so big as Treherbert .’

Bowen’s body was never recovered, at least not in any identifiable form.

Leslie Williams was 28, a blacksmith by trade and a bantamweight by sport. He was married with one son. His body was recovered and then buried at sea a week after the ship went down.

It was nothing more than a quirk of fate that three of the sportsmen on board were called Williams; they were unrelated.

Charles Eugene Williams, the world squash champion, was 23, lived in Harrow, north London and described himself as a ‘sportsman’ on the passenger list. He was travelling in second class.

Williams told reporters later that he had left the squash court at 10.30pm on the fateful night and gone to the smoking room. It was while he was there, having a post-game cigarette, that he heard and felt a crash and rushed outside to see the iceberg towering 100 feet above the deck.

He jumped into a lifeboat from the starboard side and ended up aboard the rescue ship Carpathia, which took him and 704 other survivors to New York. Williams resumed his career and lived until 1935.

Both the tennis players made it onto the Carpathia too, in contrasting states of health.

Dick Williams, whose father died in the disaster, was suffering from frostbite and there was even a suggestion that amputation of his legs was mooted.

Evidently things never got that serious, and it is important to stress, for reasons that will become clear, that there is no evidence whatsoever that Behr was personally involved in Williams’ survival that night or in the coming days.

Behr’s life story, particularly the tale of how he courted his wife, Helen Newsom (also a Titanic survivor) has been written in a book by the couple’s grand-daughter Lynn Sanford. That book, a labour of love and 10 years in the making, is called ‘Starboard at Midnight’ (left) and was published last year.

Behr’s life story, particularly the tale of how he courted his wife, Helen Newsom (also a Titanic survivor) has been written in a book by the couple’s grand-daughter Lynn Sanford. That book, a labour of love and 10 years in the making, is called ‘Starboard at Midnight’ (left) and was published last year.

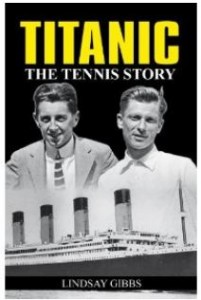

Now a new book, ‘Titanic: The Tennis Story’ (right) – already out in America but published in the UK this week – tells the stories of Behr and Williams together, focusing on their shared history as Titanic survivors and their subsequent sporting lives, parts of which were shared. They won the Davis Cup together, for example, while Williams beat Behr in the 1914 US Open quarter-final en route to one of his singles titles.

Without question it is a fascinating story, a remarkable tale of two men with so much important shared history. And yet when I called Lynn Sanford last week to talk about her ancestor, she was close to tears with frustration and anger over the portrayal of her grandparents in the new book – penned by an up and coming US tennis writer, Lindsay Gibbs.

Specifically, Sanford is upset at the way the characters of some or her relatives seem to have been manipulated for a book ostensibly produced to cash in on the 100th anniversary of the Titanic disaster.

And even more specifically still, Sanford is incensed that Gibbs has invented two key scenes. In other, Behr persuades a doctor on the night of the sinking not to amputate Williams’ legs. And in the second, when Behr has lost to Williams in the 1914 US Open quarter-final, Behr says to Williams: ‘I should have let them cut off your legs’.

This is pure fiction. It’s made up for dramatic effect. Lindsay Gibbs has told me herself that those scenes were ‘fictionalised for dramatic effect.’

And actually, when you look at how the new book is marketed, the word ‘novel’ is used in there. But whereas in Britain the ‘work of historical fiction’ is emphasised, the book is marketed as a ‘real-life account’ in the US, with the ‘novel’ element played down.

Herein lies the rub for Lynn Sanford and some (if not all) of the surviving relatives of Dick Williams.

‘I just cannot tell you how much the fabrication in the new book upsets me,’ Lynn Sanford told me last week. ‘It’s killing us. There is no evidence any of this happened. Real people are transformed into monsters for a commercial venture, to cash in.’

Both Gibbs and her publisher, Randolph Walker – a former commercial bigwig at the US Tennis Association as well as a former communications executive with the Davis Cup – stress that ‘creative licence’ is emphasised in Gibbs’ author’s notes. And it is.

Sanford just wants the record set straight to make sure a wider public know it, as she has written on her blog.

Her next public statements are likely to be on 12 April, when relatives of both men will attend an evening in their honour at the tennis Hall of Fame in Newport, Rhode Island. Both players were inducted for services to the game.

Sanford is also upset at the prospect of a commercial book with a fictional element being made into a blockbuster movie. She is even consulting her lawyers to see what if action she might be able to take in this 21st-century spat over what is essentially a battle for image rights of the long deceased.

I can see her point.

I can also see Gibbs and Walker are trying to bring a stirring story to the widest possible audience, albeit having revved up the narrative in a particularly disingenuous fashion.

But then that’s hardly new in sport, is it?

Still, when the ship goes down on TV tonight, and next week, and the week after that, we’ll remember them.

Bowen and Williams. Williams. Williams and Behr.

RIP chaps.

.