By Steven Slayford

2 July 2013

The NBA’s salary cap is well known but the league’s luxury tax is a less familiar beast – and one with potentially significant repercussions for many teams next season.

The NBA salary cap states that each team is only allowed to spend a league-set amount on wages, that number was $58.044 million for the 2012-13 season.

The association runs what is known as a “soft cap”, meaning teams are able to exceed the cap under multiple exceptions. Some exceptions are fairly straightforward: rookie contracts for first-round draft picks, signing replacements for current players who incur season-ending injuries and an unlimited number of players on the league’s minimum allowed contract.

Other exceptions are slightly more complicated: the Larry Bird exception (named after the Boston Celtics hall-of-famer), in which a team can re-sign their own player to a maximum contract as long as the player has played for that team for three seasons. Other teams are forbidden from matching or exceeding this offer.

The Early Bird exception, similar to the Bird exception except the player only has to have been playing for the team for two seasons and can only sign a new contract between two and four seasons long.

The mid-level exception, which teams can use once a year to sign one or more free agents for a maximum amount total contract. This is $5m over four years for a team who will be over the cap line but did not pay luxury tax in the previous season and $3m over three years for a team over the cap line and who did pay luxury tax in the previous season. Since 2011, teams who would remain under the cap can now use this exception to sign a player on a $2.5m contract for two years.

The bi-annual exception is similar to the mid-level exception, except it can only be used once every two years on one or more contracts that pay a total of $1.672m over two years to one or more players. Since 2011, only teams who are not did not pay luxury tax can use this.

So far, so simple.

What is the luxury tax?

As a result of each team’s ability to breach the cap in multiple ways, a luxury tax is in place to control team spending beyond the cap and ensures that teams whose wages exceed a set threshold have to pay a levy to the league. The tax threshold stands at $70,307,000 for the 2012-13 season and for each dollar an NBA team is over the threshold, one dollar must be paid to the league.

This dollar-for-dollar tax ratio was implemented as part of the 2005 NBA Collective Bargaining Agreement (a player-league labour deal) but following that deal’s expiration and the 2011 NBA lockout, a new CBA was agreed that looks set to send the luxury tax bill of several teams skyrocketing.

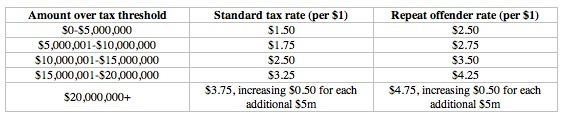

The 2005 CBA tax system was in effect until the end of the 2012-13 season but the 2013-14 season will see changes to the luxury tax bands and a sliding pay scale (see table below). For example, if a team were to be $13 million over the tax threshold, they would pay a rate of $1.50 on the first $5m, $1.75 on the second $5m and a rate of $2.50 on the remaining $3m, leaving them with a tax bill of $23.75m rather than the $13m they would have paid in the previous season.

A repeat offender rate will be introduced from the 2014-15 season. A ‘repeat offender’ is defined as a team that has paid luxury tax in all of the three previous seasons. From 2015-16 onwards the rate will be paid if the team has paid tax in three of the four previous seasons.

In view of reducing their bill, as well as applying the multiple salary exceptions, a team can elect to amnesty a single player’s contract to exclude them from being counted towards their luxury tax bill. The player will then be waived/released from the team’s roster but will continue to be paid their guaranteed salary. However, in order to amnesty a player, the player must have played continuously for the team from July 1, 2011 and must not have had any changes made to their contract since that date. Teams may only use this provision once between now and the 2015-16 season.

Where does the tax money go?

Up to 50 per cent of the revenue generated by the league through luxury tax may be distributed among teams who remained under the threshold. However, there is no requirement that states the league has to do this. At least 50 per cent of the remainder of the tax money will be used by the NBA for “league purposes”.

“League purposes” can apply to any number of things that the NBA wishes to spend their money on. For example, during the 2011-12 season the league used 100 per cent of the tax revenue to fund their revenue sharing programme, a programme which seeks to level the financial playing field between teams who can generate huge amounts in big markets ( Los Angeles, New York, Chicago) and those in smaller markets (San Antonio, Memphis, Charlotte) who cannot.

It achieves this by asking each team to send in a percentage of its profits into a common pool and then sees each team receive a 1/30th share, meaning smaller teams receive more than they contribute and vice versa for the larger teams.

At the start of the 2012-13 season, the league spent 50 per cent of the luxury tax money on the revenue sharing programme and split the remaining 50 per cent equally between the teams under the tax line. This is set to continue into the 2013-14 season but will be reviewed come the end of the 2014 play-offs.

What is the aim of the tax?

The luxury tax aims to curb team spending across the league so that no single team can, in theory, buy their way to the title. This attempt to ensure a good level of competition, however, still falters in practice as teams are still willing to breech the limit. All six NBA teams over the tax threshold for the 2012-13 season made it to the play-offs.

In fact, 12 of the 15 highest paying teams reached the playoffs. Of the 15 lowest paying teams in the league, only four made it to the post-season. The more you pay, the better players you have, the better you perform.

On the other hand, the tax – alongside revenue sharing – does allow for a levelling of the playing field between big market and small market teams, a status decided by city population and TV audience and, therefore, a team’s ability to generate money. The 20-year, $3 billion television deal that the Los Angeles Lakers signed with Time Warner in 2012 is a prime example of big market benefits.

Ten of the teams who made it to the play-offs were big market whereas six were small market. Come the next round, the split was four-four and the conference finals contained three small market teams and one big market team. It would seem that the luxury tax paired with revenue sharing does work in negating the domination of the big cities and ensuring that a wider section of the population can enjoy a high level basketball.

Does a luxury tax work better to level the playing field than FFP will?

It is the success of this method in increasing competition between larger and smaller teams that bring into question UEFA’s Financial Fair Play regulations, are now in force but will see the first ‘break even’ successes and failures confirmed in the coming season. While Michel Platini et al have extolled the virtues of their new system, many have pointed out the potential for FFP merely to entrench a group of haves and have-nots.

Simple logic suggests that European clubs only being allowed to spend the money they, as an organisation, generate will surely see teams with like Manchester United, Barcelona, Real Madrid and Bayern Munich with their worldwide fanbases, multi-million sponsorship deals, prize money from the Champions League and huge television deals leave other ‘lesser’ clubs trailing in their wake.

The imposition of a luxury tax system – not being mooted other than hypothetically, here – would not only limit the spending power of those biggest clubs but also improve the ability of smaller clubs to compete. Some form of salary cap would also make a difference, not that European law would allow it, almost certainly.

But imagine if Manchester United were not only being prevented from paying much bigger salaries to multiple players but having to channel the money they would have spent on those salaries to teams in the bottom half of the table. It would certainly give a little more validity to the term “competition” when talking of the Premier League.

Ridiculous? It’s what happens, and will happen, in the NBA.

Competitive balance

The salary cap and luxury tax has seen the NBA title lifted by six different teams in the last ten years while the Premier League has had four, the Bundesliga five and La Liga and Serie A have only seen their title raised by three different sides. Imagine a football season starting with 12 or 13 serious title contenders. A cap and tax system allows for that.

The main issue with FFP is: how will punitive measures be taken against teams that breech the regulations? Platini himself has been evasive in answering this and suggestions have ranged from points deductions to exclusion from European competitions.

With the luxury tax, financial measures are imposed at the beginning of each season and then every time a team’s salary situation changes. There is no uncertainty and plenty of transparency. Each team knows where they stand and is aware of what will happen once the rules are breached, perhaps something UEFA should take note of.

What do the changes mean for the NBA’s biggest teams?

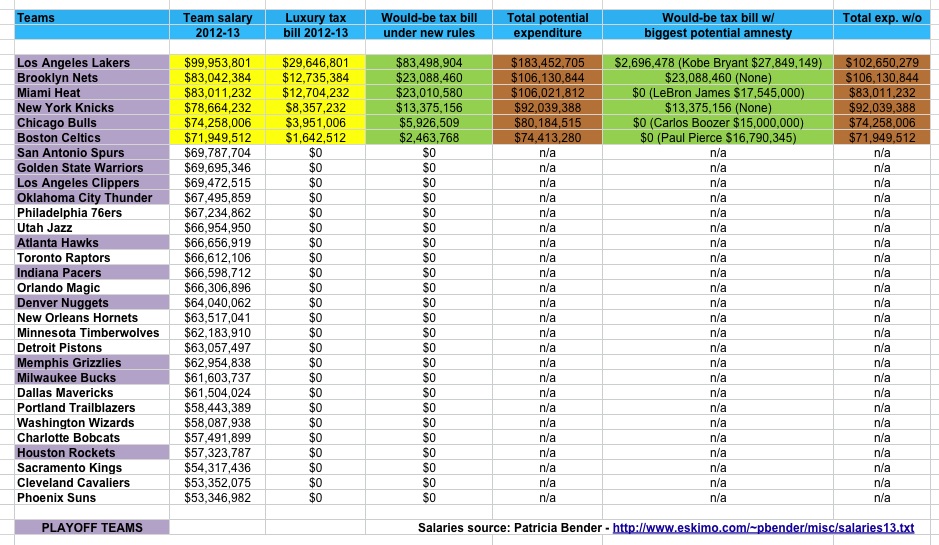

Next season’s NBA salary totals cannot be predicted exactly but below is a table that shows what would happen if the teams currently paying luxury tax carried their current salary totals over to next year.

Article continues below

The Los Angeles Lakers would find themselves in the most perilous position under the new rules, with their tax total almost matching their incredible wage bill to take their total salary outgoings to over $183m per season. However, there is no guarantee that big-name center Dwight Howard will re-sign in LA and if he were to move elsewhere that would see around $20m wiped off the Lakers’ wage bill and keep the team’s luxury tax bill to a far more manageable level. But, if Howard stays, there is another potential saving thanks to Kobe Bryant’s Achilles injury.

The five-time NBA champion could miss the entirety of next season and is eligible for amnesty. This would mean the shooting guard leaving the Lakers and the team having to wait until 2014 to sign him under amnesty rules. Los Angeles would also waive their “Bird rights” and could see Bryant offered more lucrative contracts elsewhere. The move would perhaps be unpopular among fans, especially the idea such an icon would simply be seen as a financial strain, but if the team could get Bryant himself on board they could be looking to save $80m for the year in tax alone, a figure that cannot be ignored even for such a wealthy franchise.

The Brooklyn Nets, a team with no amnesty options, would see their tax bill soar to almost double last season’s total and move their total expenditure on player’s wages alone to well over the $100m mark for the year and could find themselves with the highest outgoings in the league.

However, with the trades of Kevin Garnett, Paul Pierce and Jason Terry confirmed from Boston and Kris Humphries, Gerald Wallace, Reggie Evans, Kris Joseph and Keith Bogans headed the other way, the Nets have already wiped $8m off last season’s total, mainly by relieving themselves of Wallace and Humphries $10m+ contracts. It would seem that the new rules are already firmly in the mind of owner Mikhail Prokhorov.

The Miami Heat would also see their expenditure level move to the same height as the Nets but with several amnesty options available to them. However, with the most expensive three of those options being the $17m+ contracts of Chris Bosh, Dwyane Wade and current MVP LeBron James, the three blades of a propeller that have pushed the team to its second NBA title in a row, it would seem wildly unlikely that the Heat would take any of those options. Mike Miller does provide another amnesty option. Then again, a $10.3m increase in yearly tax is certainly one that a franchise reportedly worth $425m could absorb.

Further down the scale, the Knicks would see only a slight increment in tax of around $5m and with no amnesty options and a desire to build on this season it would seem that New York would be willing to accept the rise. The trade of Andrea Bargnani from the Toronto Raptors for Marcus Camby, Steve Novak and Quentin Richardson has seen the Knicks reduce their total by $1.2m and signify a prudent but ambitious pre-season for New York.

The Chicago Bulls have decisions to make on the expensive contracts of Carlos Boozer and Luol Deng after a relatively disappointing campaign. The return of superstar Derrick Rose could hasten any such decisions but the new luxury tax rates are unlikely to be an influence on a franchise with a $2m rise if salaries were to stay the same.

The Boston Celtics have for some time been linked with the phrases “restructuring” and “overhaul” but no-one could have quite believed that they would trade out Garnett and Pierce almost as soon as the season was done. The $8m increase they have received from their new acquisitions also presents a new problem but many have speculated that Rajon Rondo may also be looking to jump ship this summer and the removal of his $11m contract to a team with cap space could move the Celtics’ tax to a more reasonable level.

It is also interesting to note that while every team that is currently over the tax threshold made it to the play-offs only one – the Miami Heat – has made it to the Conference finals, proof that overspending is no guarantee of success.

While this profligacy is being punished on-court through lack of success, the new sanctions will mean that the off-court penalties will soon be too high to ignore and a successful team between the hoops will now need to be a successful team on the books.

Steven Slayford blogs on football at footballsimple.wordpress.com and on basketball at http://highhoops.tumblr.com. You can follow Steven on Twitter at @sslayford

More on The NBA (or search for anything else in box at top right)

Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter