.

The days when the world heavyweight title was routinely feted as the ‘richest prize in sport’ may be long gone, drifted east in its increasingly fragmented forms before coagulating as the sole preserve of a pair of precipitous Ukrainian brothers who swat all-comers with nonchalant ease. But the chance to fight for the same title which can be linked back to the unanimous belt once claimed by genuine legends from Jack Johnson to Mike Tyson and the 21 more-or-less instantly recognisable names in between, remains, for most heavyweight boxers, the fulfilment of a lifelong dream. As MARK STANIFORTH recounts, for one fighter, Tim Tomashek, it was a dream achieved 20 years ago this month in extraordinary fashion. Read Mark Staniforth’s blog here

.

.

5 August 2013

It’s unlikely Tim Tomashek, a flabby, mullet-haired club fighter from Whiting, Indiana, a city best known for its annual ‘pierogi fest‘ – effectively a raucous celebration of savoury dumplings – could have summoned such a scenario even in his most far-fetched of sleeping hours.

Tomashek was in many ways the physical manifestation of his home city’s lip-smacking obsession: reveling in the nickname ‘Doughboy’, Tomashek clomped the mid-west looking to lasso bouts that would earn him little acclaim and even less loose change: he once bragged that he fought in South Dakota for a crate of beer.

There are no end of popular myths that have sprung up in the 20 years this month since Tim Tomashek clambered in the ring to challenge Tommy Morrison for the heavyweight championship of the world.

Yes, that’s the heavyweight championship of the world. You can paint the minor details up exactly how you wish – and plenty have – but the stone-cold fact is on 30 August 1993 at the Kemper Arena in Kansas City, a tubby and (presumably) pirogi-loving journeyman called Tim Tomashek clambered in the ring to fight for a version of the same title once held by Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis and other such fistic luminaries.

Tomashek’s name rests proudly beside them in the record books; you can see the fight on YouTube (below).

Article continues below

Tomashek was duly worked over by Morrison, a heavy-handed, blond-haired heart-throb from Arkansas who, as the latest incarnation of the fight game’s great white hope, would go on to fight Lennox Lewis before his career petered out in the late 1990s when he tested positive for HIV.

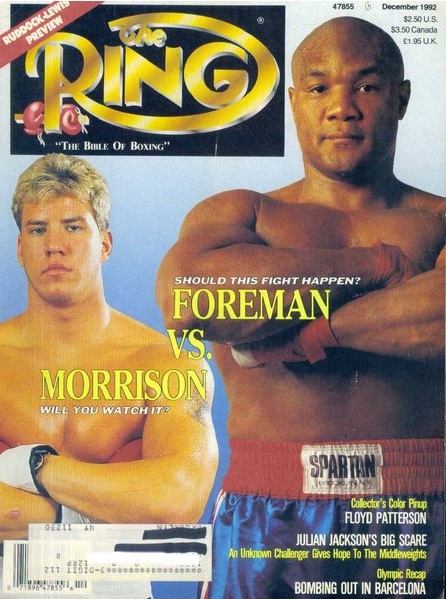

Tomashek was retired on his stool at the end of round four: Morrison went about his business with the casual disdain of one aggrieved at being hoodwinked into playing any part in such an unseemly affair. Morrison had, after all, won the vacant title by beating the somewhat more notable George Foreman only two months earlier in a bout that made front page news (right).

Afterwards, an irritable Morrison paid Tomashek the ultimate non-compliment: “I didn’t know I was fighting Whatsisname until I got out there,” said Morrison. “It wasn’t difficult. The guy was basically in there to survive.”

Tim Tomashek was probably not the worst man to ever fight for the world heavyweight title. His record heading into the Morrison fight was an almost respectable 35 wins against 10 defeats.

True, most of those wins had come against dusty cow-pokes with or without a crate of booze at stake, but Tomashek had also taken the perennial South African contender Francois Botha ten rounds, and could just about stretch to calling himself an international fighter: he once accepted an invitation to fly to France to lose to a local cruiserweight called Anaclet Wamba. “I saw some sights,” recalled Tomashek. “It was awful nice.”

Tomashek might have stood a chance against one or two of Joe Louis’s more notorious ‘Bums of the Month‘ and he didn’t demean himself quite so much as Jean-Pierre Coopman, who sipped champagne in between rounds of his fight with Muhammad Ali in Puerto Rico in 1976.

The advent of the little-regarded World Boxing Organisation in 1989 paved the way for any number of questionable contenders, including a Topeka cruiserweight called Damon Reed, whose ‘Dangerous’ epithet would have got him pole-axed under the trade descriptions act, if Herbie Hide hadn’t taken 52 seconds to get there first (I would also mention the South African Johnny Du Plooy, who was floored in three by Francesco Damiani for the inaugural title in 1989, but Du Plooy picked himself up to deck Tomashek himself in five the following year).

In the context of such unilluminating company, what marked out Tim Tomashek as an especially surprising heavyweight contender was not so much his stellar lack of qualification for such an historic honour, but the circumstance in which he was afforded it, not to mention the way in which, while his bruises healed, he proceeded to milk his 12 minutes of fame for all it was worth.

In the context of such unilluminating company, what marked out Tim Tomashek as an especially surprising heavyweight contender was not so much his stellar lack of qualification for such an historic honour, but the circumstance in which he was afforded it, not to mention the way in which, while his bruises healed, he proceeded to milk his 12 minutes of fame for all it was worth.

The way Tomashek told it – and he would prove much better at telling it than fighting it – he had finished his shift as a forklift operator at a local department store when he took a call from his boxing manager.

“He says, ‘Hey, do you wanna fight Tommy Morrison?’,” Tomashek told the Chicago Tribune in 1993. “Well, I’ve heard that kind of thing before, so I said, ‘Naw, I want to go to the Packers tailgate party.’ He says, ‘They’ll pay you $2,500 just for showing up here.’ I’m out the door.”

Tomashek was flown in ostensibly to act as a potential substitute for Morrison’s scheduled opponent Mike Williams, a mentally suspect fighter who had the promoters running scared after failing to show up for a number of scheduled media appearances.

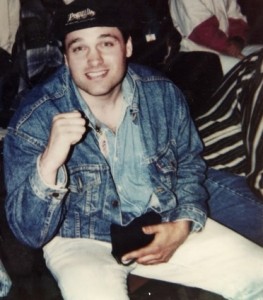

Tomashek duly sat in the crowd (above) and, as some versions of the story would deliciously have it, started chomping on a hot dog. With the undercard well underway, he was tapped on the shoulder by the well-known respected Bruce Trampler, who told him Williams had refused to fight.

Tomashek duly waded back-stage, presumably having swallowed his last gob-full of bun and wiped the ketchup splodge off his shirt. Less than two hours later he re-emerged, grinning and waving to the crowd, looking every inch the guy who never dreamed the day might come when he would get a short-notice shot at the heavyweight championship of the world.

Read Mark Staniforth’s blog here

Again, while Tomashek’s situation was unique in terms of the world heavyweight title, in the sport as a whole it was not entirely without precedent. In 1969 a New York journeyman called Charley Green was pulled from the crowd to fight Hall of Fame light-heavyweight Jose Torres at Madison Square Garden. Green accepted, on the proviso the promoter added an extra $16 to his $3,000 offer – the price of his ticket and his hot dog (note the ubiquitous fast-food reference: could it be that canny match-makers make sure to pluck prospective last minute replacements from the ranks of those who do not see the need to watch their diets?)

Wearing trunks rushed to him from a nearby gym, Green proceeded to knock Torres down and almost out at the end of the first round, and again early in the second, before being stopped himself.

In 1999 Californian flyweight Isidro Garcia went one better. Garcia settled in at the appropriately-named Fantasy Springs Casino in California expecting to watch a world title bill and was plucked from his seat (while – wait for it – chewing on a donut) to face WBO champion Jose Lopez in the main event. Garcia scrounged a spare pair of trunks, a protective cup and a mouthpiece, and proceeded to dethrone Lopez via unanimous decision. “Someone’s looking over me,” said Lopez afterwards. “What a Christmas present”.

But neither Green nor Garcia shared Tomashek’s knack for making the most of the moment (certainly not Green, who went on to serve multiple life sentences for murder).

Tomashek grinned and gurned his way through the bout, and made a good job of over-protesting when he was pulled out, insisting: ‘I’m okay!’ and orchestrating the crowd as they booed and began tossing ice and cups in the ring.

Afterwards Tomashek reeled out some sharp one-liners. Asked how he trained for the fight, he said: “They beat me up at work”. Asked why he believed he had got the call, he said: “They knew I’d put up a good tussle – or else they like bloodshed.”

Asked what was the best thing about fighting Morrison, he replied: “Not having to wait in line to get tickets.”

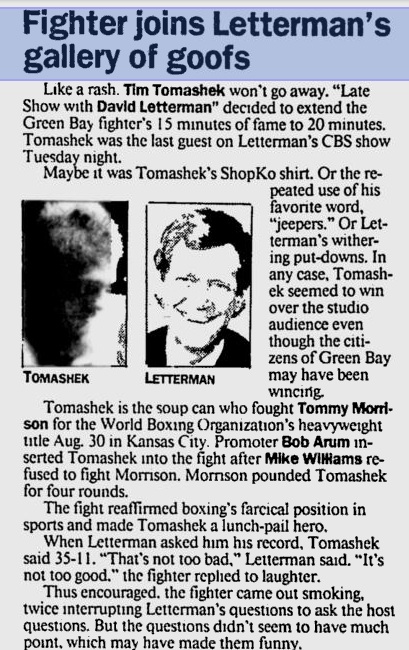

In the week that followed, Tomashek was invited on the David Letterman show, where he was roundly ridiculed for using the word “jeepers” 12 times in the course of their less-than-five-minute segment.

At one point Tomashek leaned in to interrupt his host as as started to ask a question, and asked Letterman if he lived on a certain street in Indianapolis. When Letterman replied that he lived on a different street, Tomashek said: ‘Hh, that cost me five bucks’, explaining he had once paid a cab driver five bucks to show him Letterman’s house, but had evidently been taken to the wrong place.

Tomashek’s mock indignation at being cheated out of such an inconsequential sum of money somehow exacerbated the farce of his fight for the so-called richest prize in sport: it was supposed to set him up for life, and here he was bitching about five bucks. Letterman replied: “You took a real hard one to the head, didn’t you?”

The peculiar carnival quickly subsided, but it didn’t do Tomashek’s immediate prospects too much harm. Two months after his fight with Morrison he was back in Kansas City to beat a novice called Gary Shull, and he embarked on a run of 16 straight wins, beating guys like John Basil Jackson, who would finish his career on a forty-fight losing streak, and Winston Burnett, a Welshman who had lost ten straight and whose eclectic career almost matched that of Tomashek, having been afforded the painful honour of being knocked out twice in the same year by Nigel Benn.

Tomashek won his last bout at the Veteran’s Coliseum in Iowa in February 1996 against a one-fight-winning opponent called Ken Doss, a name that half-evokes the image of an ailing old ventriloquist act. It seems oddly appropriate: after all, hadn’t the mullet-haired mauler from pierogi-town spoofed his way to a shot at the world heavyweight title, and right back home again?

Twenty years on, back in the relative anonymity of his factory shift work, it’s a tale Tim Tomashek has every right to continue to grow fat and old on.

Mark Staniforth is writing a novel about boxing. For more see here. Read Mark Staniforth’s blog here

.

As Mayweather prepares for Canelo: the lessons and perils of boxing’s lethal secret