.

7 January 2015

You almost certainly had no knowledge that it was happening, let alone followed it closely, but events at a cyclocross World Cup event held last month in Namur, Belgium, highlighted the ongoing disparities between the treatment of men and women in global professional sport. And this happened in cycling, where the world governing body, the UCI, is theoretically in support of pay equality and apparently working towards it, but where equal pay has been implemented for some of its races but not others.

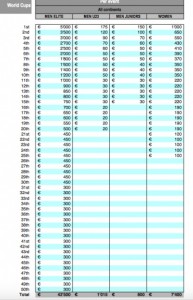

In the event in Namur, 50 elite men took home winnings but only 25 elite women. The men’s prize fund was €42,500. The women’s was €7,400, or about one-sixth the size (detailed in table, right, click to enlarge). And the size of the entry list for the two races was close to parity, so no excuse can be made that fewer women compete.

Jonathan Page, an American who finished 18th in the elite men’s competition at Namur, noted in a tweet that in a World Cup event the 50th place elite male, five laps behind the winner, earns the same as a 7th place woman in the same race. He then asked: “WHAT?? Is it 2014 or 1950?”

Helen Wyman, a professional racer who is the eight-times British and twice European champion, has Tweeted on the same theme and her blog on the subject, highly recommended, contains some eye-opening statistics about her sport.

Wyman notes that over the course of a season, in World Cup events the UCI will pay out more than €20,000 to non-competitive male racers (those who are lapped on a cyclocross course), which about 50 per cent of the total World Cup purse available to women.

Incidentally, inexplicably and extraordinarily, at the Namur race elite women were not allowed to park their cars in “elite parking”. It was reserved only for men.

Even some of the biggest events in the most mainstream and globally popular sports have only dragged themselves into the 21st century late on. It was as recently as 2007 that Wimbledon and the French Open became the last two tennis grand slams to pay out equal prize money to both women and men. The decision by Wimbledon capped a long debate in tennis over whether women and men ought to receive the same winnings. The debate had raged since before the US Open gave out equal prize money in 1973. What has happened most visibly in tennis has also occurred across sport.

At the institutional level, the debate over equal pay in international sport appears to be over. For instance, the International Olympic Committee, which coordinates the various national committees and federations of the many Olympic sports, expresses in its Charter as one of its roles “to encourage and support the promotion of women in sport at all levels and in all structures with a view to implementing the principle of equality of men and women.” This text was added in 2007.

The evidence shows that most sports organizations are in line with the principles of the IOC. Last October the BBC surveyed how 56 sports governance bodies allocated winnings to men and women and heard back responses from 51. Of these, 14 do not pay winnings, 27 pay winnings equally to men and women and 10 do not pay equally. Among the sports that pay equally are athletics, skiing, swimming, triathalon and marathon. Sports that do not pay equal prize winnings include cricket, squash, football, surfing and cycling.

Cycling is particularly interesting. The UCI Athletes’ Commission has proposed equal prizes for men and women, and the UCI has partially implemented that recommendation. The UCI Constitution says that it carries out its activities under a principle of “equality between all the members and all the athletes, licence-holders and officials, without racial, political, religious, or other discrimination.” In words, if not in deeds, the issue of equal pay has already been decided by the UCI leadership.

The issue of equal pay in global sport is no longer about men versus women. For instance, the equal pay debate used to focus on issues like the significance of different formats. In the grand slam tennis events, women play the best of three sets while men play the best of five. In cyclocross, races are one hour for men versus 40 minutes for women. While online and pub debates will no doubt continue to explore such issues, for sports organizations, they have mostly been resolved.

I say mostly because there are plenty of women in tennis and cyclocross, Helen Wyman included, who would be happy to compete in the same format as their male counterparts. Such format-sharing takes place in athletics where women and men compete in equivalent events, including in the marathon. The shorter formats for women in some sports are vestiges of a bygone era where women were thought to be too delicate to participate in the same events as men.

Today, the issue of equal pay for men and women in sport is more about accountability than gender. So long as sports organizations like the IOC and UCI invoke equality as a guiding principle, then they should be held to those principles.

That is not a matter of gender equality, it is simply a matter of good governance. Alternatively, if the leaders of these organizations actually believe that women should receive smaller purses for their competitions, then these leaders should have the courage to change the stated principles of the organisations that they lead to reflect those beliefs. Saying one thing and doing another is not a successful course of action for any institution.

In sport, equality in competition may actually be a lesser problem than equality in governance. In a 2013 survey of 1,550 people in leadership positions in international sports organizations, SportAccord found that only 13 per cent were women; and 25 per cent of institutional executive committees included no women at all. Perhaps that helps to explain why in some sports organizations completing the task of matching deeds with words on gender equality is taking a while.

.

Roger Pielke Jr. is a professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado, where he also directs its Center for Science and technology Policy Research. He studies, teaches and writes about science, innovation, politics and sports. He has written for The New York Times, The Guardian, FiveThirtyEight, and The Wall Street Journal among many other places. He is thrilled to join Sportingintelligence as a regular contributor. Follow Roger on Twitter: @RogerPielkeJR and on his blog

.

Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter