29 February 2016

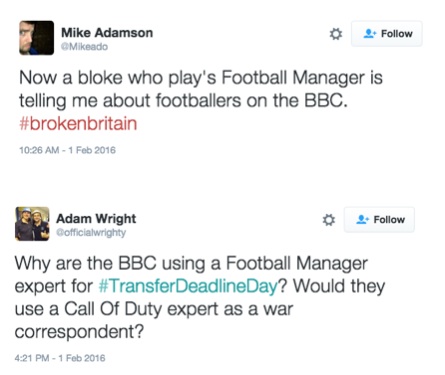

TRANSFER deadline day this year was its usual mixture of hype, desperation and the occasional genuinely interesting deal. And of course, for me, abuse. For the last three deadline days I have been part of the BBC’s live blogging effort, offering a Football Manager perspective on the day’s comings and goings, proposed or actual, and attracting as much criticism and opprobrium as any club signing Roger Johnson would.

.

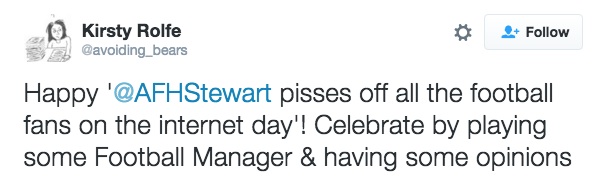

Not everyone was hysterically upset.

.

.

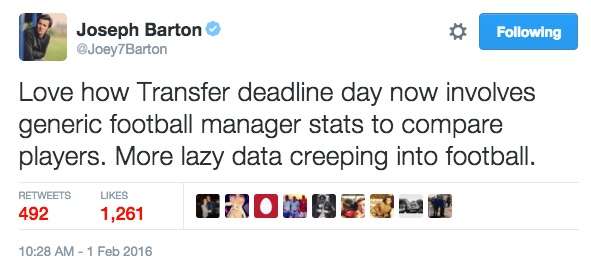

Even Joey Barton took to social media to comment, saying on Twitter:

.

.

Assuming that what Joey means here is lazy use of data, his criticism was echoed widely and fits neatly with a general narrative prevalent among some football fans that data are misused, either as shortcuts to understanding players or as throwaways to support an argument.

The narrative runs thus: There’s no substitute for experience at a high level of football or the eye of a ‘proper football man’, whether one’s looking at player recruitment or tactical analysis.

Now as someone who plays FM, I’ve fired up the latest version and looked at Burnley’s staff, as of the beginning of the 2015-16 season. They’ve got Sean Dyche as manager, Tony Loughan as coach, and Jason Blake as the man in charge of youth development. Living, breathing, real people. There’s chief scout Glyn Chamberlain, again a real person.

I can also infer that 21-year-old striker Chris Long is the most likely prospect in Burnley’s ranks to progress well over time, and that 18-year-old striker Dan Agyei, a youth-team player, also has a good chance if he can overcome his stamina issues and use his natural pace and acceleration.

I know that Burnley have good training facilities but might invest further in their youth system and, at the start of this season, they had a good chance of finishing in the play-off spots, but probably no higher. (In that respect, they are in fact exceeding expectations by being top of the Championship as things stand, although they have played two games more than Middlesbrough, who are two places and one point below them).

I can even tell you that Joseph Anthony Barton is determined, hard-working, and at 33 years old, a bit slower than he was earlier on in a good career. He also has a ‘volatile, outspoken’ media handling style, though I’m not sure I needed FM to confirm that. It’s a lot of information.

All clubs in the upper echelons of the (real) game now use data-driven recruitment tools. I asked Burnley about theirs and although they didn’t want to go into details, a source explained they are in the process of beefing up their analytics portfolio. They currently do not use ProZone’s Recruiter, but it’s on their radar and being considered.

Many clubs already use it, including quite possibly some that Joey has played for.

And Recruiter is partly driven by the most comprehensive database of player information in world football. Which database? The one developed and maintained by Sports Interactive, the company who make Football Manager; the one that underpins the game.

In effect, the data gathered by S.I. is already being used by many clubs to help inform transfer policy and, if they’re not using S.I.’s database, they’re using something a lot like it.

Joey might see it as lazy and a gimmick for the BBC’s coverage, but analytically-based decision making is already very real in football as part of a matrix of information that clubs use to help buy and sell players.

Of course, analytics of this sort isn’t the only piece of the jigsaw and there’s much to be said for physical scouting of players. But, in a globalised football world where the reach of clubs has expanded enormously and the competition to find the next Messi is fierce, having means to whittle down a potential list of signings or identify attributes or skill-sets that fit a team’s make-up and intended style of play is crucial if clubs are to stay on or ahead of the curve.

A recent Mail on Sunday feature (right) went into some of this, but I wanted to delve a little deeper and explore just how accurate the simulated world of Football Manager is and how it’s achieved.

The Football Manager database was created in 1992 and comprised some 4,000 players and non-playing staff. That figure now stands at 651,952, of which 325,548 are listed as being at a club, and most of whom are current professional footballers or coaches; retired players and other club staff are also included.

There are 39,000 active clubs, of which around 2,250 are researched in depth by the Football Manager team: that’s a span of 116 divisions across 51 countries. In addition, a further 2,000 clubs from those 51 countries are covered in less detail, and there is information on the top clubs from every other country in world football as well.

This information is gathered and managed by a Head of Research and his full-time team of six, bulked out by a further 70 Head Researchers and a team of on-the-ground scouts that fluctuates but usually numbers around 1,300. It’s a complex, thorough undertaking, regularly quality-assured with algorithms and query-based programs that check the database for statistical outliers or anomalies; the database is also updated five or six times a year to keep it current and responsive. Lazy, it isn’t.

Of course, judging the ability of a seasoned pro is easier than peering into the crystal ball and trying to assess where a 16- or 17-year-old might be in 10 years’ time. There are many reasons why a player could fail to realise even a very obvious potential ability: injury, personal problems, being supplanted in the team by a new signing or an even better prospect, a change of management, a tactical system that sees them sidelined; the list is endless.

Generally, a player peaks around 27 or 28, possibly goalkeepers aside, so a look at the players with world-beating potential from FM2005 is instructive: for every Carlos Tevez, Philipp Lahm, or Vincent Kompany, there is a Kostadin Hazurov, Johan Vonlanthen, or Jonathan Legear. Some players, like Steven Taylor or Anthony Vanden Borre have had solid pro careers without igniting but some, like Javier Mascherano or Cesc Fabregas, have been exceptional.

Miles Jacobson, the studio director of Sports Interactive and Football Manager’s head honcho, recognises the complexities that come with assessing a player’s potential.

“It’s extremely difficult,” he tells me. “Because their raw ability goes hand in hand with their mental attributes, training facilities, coaching staff and many other factors.”

The designated club scout will provide the first data set for a player. This initial input from scouts is crucial, and they have a broad remit, as Jacobson explains. “The first line is the initial scout’s judgment. Our scouts don’t just attend senior, reserve and youth team games, they’re also active on social media and official and fan forums, so they’re working from an extensive knowledge base.”

These values which are then checked by the Head Researcher, who compares that player with others from the club and nation, assesses the scout’s rating and consults them if it is felt that the numbers are too high or too low. The internal research team also compares the player with other, similar players to see again if his potential is something of an outlier, or fits sensibly within the broader picture of the world game. The player is constantly reassessed, as Jacobson explains. “As a player gets older and gains more experience we constantly reassess his PA (potential ability) along with all of his individual ratings. This PA usually becomes a fixed figure at some stage in a player’s early twenties.”

The process continues even once the relevant game-driving database is available for public use. “Once the data is released to the outside world (within Football Manager), it’s subject to the rigorous quality control of millions of pairs of eyes who constantly feed back through our forums and social media,” Jacobson says.

Of course, as the above list of FM 2005 players shows, even this thorough process of gathering, checking, and rechecking data doesn’t guarantee that a player will progress. FM folklore is full of players like Freddy Adu (left), Cherno Samba, or Mark Kerr who were astonishingly successful in the virtual world of the game but failed to translate that into real world success.

Of course, as the above list of FM 2005 players shows, even this thorough process of gathering, checking, and rechecking data doesn’t guarantee that a player will progress. FM folklore is full of players like Freddy Adu (left), Cherno Samba, or Mark Kerr who were astonishingly successful in the virtual world of the game but failed to translate that into real world success.

These players, while often loved by the Football Manager community, are ready fodder to the argument that Football Manager often gets it wrong. Jacobson defends the database’s predictive qualities against that charge, saying: “Even the best managers get it wrong sometimes – and our strike rate is way higher than most. Players like Cherno and Freddy Adu actually made us look at the entire way we judge potential, though.”

The behind-the-interface potential rating used to be a fairly unsophisticated binary opposition: 1 meant ‘will make it at a decent level’; 2 meant ‘will become a world star.’

This measure has evolved into a much more complex system, which has led to a more realistic future reckoning of ability, as Jacobson explains. “The system now has 20 ‘randomisers’, from 1 to 10 with 1.5, 2.5 etcetera in between. There might be one player in the world at any one time who gets a 10, which would be a ‘world star’ player – we simply had too many potential world stars 10 years ago. We don’t have that now.”

The regular, fluid assessment process, whose fruits are, of course, only seen twice a year by players of the game, means that there are fewer Chernos and Mark Kerrs, but also that the game functions far more realistically as a guide to potential ability.

And a player like Freddy Adu, still only 26, is not a write-off either. As Jacobson argues: “[Freddy] still has lots of potential – he just hasn’t got close to reaching it yet. So whilst he won’t get to the stage everyone in the football world thought he would get to, he’s still got a chance of making it at a decent level, given his age.”

There is, of course, a danger that as the game’s database gets bigger and more accurate, the anomalies like Cherno Samba disappear and with him, part of the game’s appeal. But the game’s increasing sophistication and its vast network of scouts means too that as a barometer of a player’s potential, it is only getting better and more accurate.

No system will ever be perfect and only the most ardent FM fan would ever suggest that the game is a flawless guide to the future of football, but the database’s use in tools like Recruiter shows that, even if some fans, and players, haven’t yet bought into it, much of the rest of football is doing so.

.

Alex Stewart is a freelance writer, mostly about sport, particularly football, and also reviews books and theatre. See a portfolio of his work here. Follow him on Twitter @AFHStewart He also worked as a stats journalist and analyst for the Rugby News Service at RWC2015.

.