By Nick Harris

31 October 2016

The 1998 Tour de France was utterly overshadowed by drugs busts and irrefutable evidence of widespread cheating. This was apparently a new low in the global landscape of doping scandals. Apparently is the operative word.

It would be a long time before the truth about cycling’s real doping problem emerged. Some might argue it still hasn’t, fully. But in that autumn, 18 years ago, The Independent sports desk undertook to try and gauge more about the ‘real’ situation about doping, in British sport at least.

It might sound naive now, perhaps even destined to reveal nothing, but we wanted to attempt to survey elite sportspeople and ask them for their experiences and views on performance-enhancing drugs. It was my idea; I oversaw the project, collated the replies, crunched the data, co-ordinated the follow-up interviews and articles and features that we ended up running.

This recap now is down to a tweet by Denise Bayliss (@DeniseBayliss), who tweeted on 29 October an article from many years ago citing reasons that the British Cycling Federation gave at the time for not taking part. Here’s that article:

.

*

It’s almost amusing now to note that the article says: “Peter Keen, director of cycling’s World Class Performance Plan, thought academics, not journalists, should compile such a survey.”

Cycling as a sport was shot through with a drugs culture that was deep-rooted and widespread, if not quite to the extent that every top cyclist was doping, but almost. British sporting hero and cyclist Tommy Simpson had been a 1960s doper who died in part due to his doping.

The notion that cycling, or British cycling, was somehow ‘clean’ by the 1980s and 1990s, or specifically by 1998 when the survey was done, is risible. Indeed, when I did a much later investigation into doping in cycling, in 2012 after the USADA cycling investigation snared Lance Armstrong (and do devour all the USADA files if you never have), it was obvious British cycling still had the most stubborn, deaf-dumb-blind approach to acknowledging doping had ever happened in British cycling.

Without digressing too much, that 2012 investigation touched on Team Sky, their ‘zero tolerance’ policy, senior staff and coaches who were formerly riders, as well as a wider group of contemporary personnel in British cycling (British and non-British) who had ridden together – and doped together – in the late 1980s and 1990s. They know who they are, these former dopers bonded by their omerta. Some are still in senior positions, some not, and some recently not. What they did back then was, in the grand scheme of things, not such a big deal in itself: we’re talking about banned amphetamines and testosterone mostly, and perhaps a few of the more sophisticated ones dabbled as early-adopter EPO users in the early 1990s. Stuff that many if not all riders were doing.

What’s fascinating even now is how they can’t / won’t / don’t acknowledge it and talk about it, publicly at least. Even now in late 2016, few involved are ready to have a grown-up, full disclosure conversation about drugs in sport. And they certainly weren’t really in 1998 when we did our survey. So apologies to Peter Keen, but it was a bollocks excuse that British Cycling preferred someone else to probe the issue. They wanted nobody to probe. They still don’t.

But the Drugs in Sport survey, across the sports that did take part, was a worthwhile exercise in any case.

We never expected to get hundreds or even dozens of sportspeople to tell us about their own drug taking. But we were interested in their own experiences and perceptions of doping in their sports.

Methodology

The Independent was a British paper with a largely British readership – this was a time when the internet was still developing and most readers still consumed the paper on paper. Yes – in 1998!

So our panel of potential respondents came from sports of interest to our demographic of readers, namely football, cricket, two rugby codes, athletics (track and field), swimming, (athletics and swimming being the two main Olympic sports), horse racing (jockeys, not horses), boxing, snooker, rowing, cycling and weightlifting. We enlisted the help of governing bodies and / or unions to send the questionnaires (on paper, with a FREEPOST reply envelope) to the home addresses of almost 1,400 British sportsmen and sportswomen.

Only the cycling and rowing governing bodies took the decision not to allow their athletes to even receive the questions. (It was always going to be an individual’s choice over whether to reply, whether to do so anonymously or with contact details and so on).

With boxing and snooker we received fewer than 10% of replies from forms sent, so did not include them in the findings. Otherwise the response rate was about 25%, which is very high for surveys of this kind. We had more than 300 responses across the sports. The level of sportsperson was a Lottery-funded elite in athletics and swimming (generally Olympic athletes), first-class cricketers, Premier League and Championship footballers, leading jockeys, Super League and Premiership One rugby players, every Briton in the top 1,000 work rankings in tennis, and international weightlifters.

Now, 18 years on, a survey of this kind and its findings seem mundane in some ways, but also revealing and a good snapshot of an era and attitudes in others.

The survey form itself was made as simple as possible to fill in – box-ticking, yes / no answers, a few spaces for additional information, and a request for the respondent to make themselves available for interview in greater detail, on or off the record as they liked.

The questions asked about their experience and use of performance-enhancing drugs, their perception of usage in their sport, their attitude to the prevailing doping rules, whether they had ever been offered drugs or encouraged to take them, and if so what. We asked whether they would take drugs if legal, and what drugs (legal or otherwise, from a list) they had ever taken, and how often. And we asked about general lifestyle and social drugs including consumption of cigarettes, alcohol and other recreational drugs include cannabis, ecstasy and cocaine.

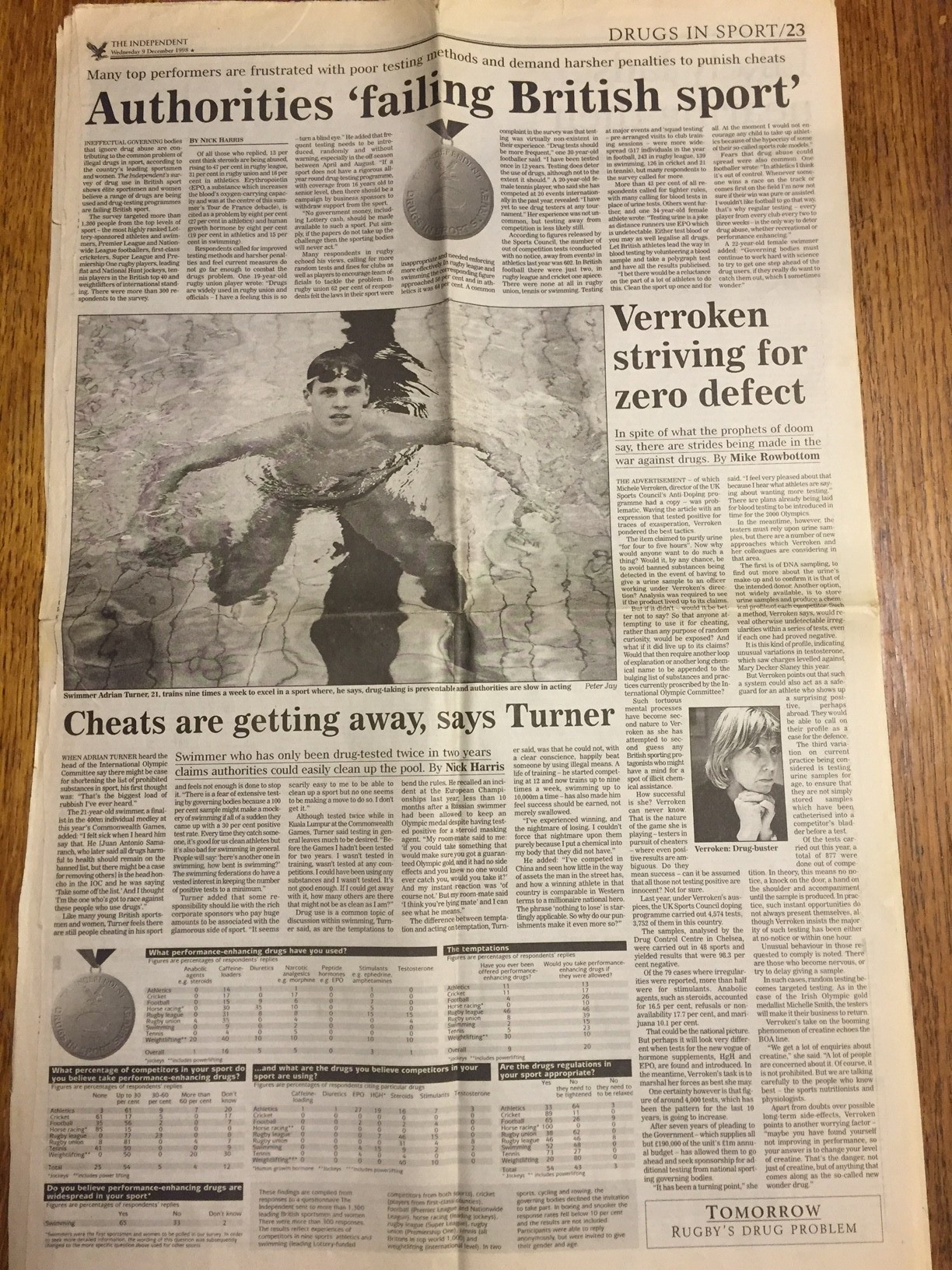

The forms came back in – in fact they’re all here, still, on a shelf in my office – and the responses were crunched. Quite a few sportspeople did in fact want to talk further, in detail, about their experiences, although not many of them wanted to be on the record for interview. Swimmer Adrian Turner was happy to talk about competing against those he knew to be cheating and his frustration. My colleague Mike Rowbottom wrote a piece in which distance runner Jon Brown talked about his fears over a relatively new drug called EPO in his sport. Welsh runner Jamie Baulch spoke openly about competing against cheats. I personally met with rugby players (both codes), a weightlifter, several footballers and various Olympic athletes to talk about their own concerns and experiences. These informed various pieces.

The coverage

Some of the coverage is online and below are some links, and further down are some of the original pages. I cannot find links to all the findings and related articles online. But the scans of the pages are mostly readable.

Looking back now, three things are striking. First, creatine was a relatively new and legal supplement at the time. It is still legal but not new. But it had taken a very short space of time for it to become almost ubiquitous across all sports despite some concerns. I think it was true and remains so, more than ever, that athletes will quickly adopt any substance that is legal and offers improvement. This isn’t a surprise, but it’s worth remembering that most top sportspeople will probably always go as close to the line as they can, legally, even if not ever minded to cross it. That appears ‘normal’.

The second striking thing was that both codes of rugby seemed to have a major drugs issue even back in 1998; it was almost as if an entire genre of sport was being transformed by drugs, mainly steroids, to the point that the physical shape of rugby players was changing before our eyes. From some of the testimony, on and off the record, it seemed doping was rife in rugby. I see no reason that should have changed; arguably it is one of the most under-explored areas of doping in sport – a sport that is arguably among the most physically demanding.

The third striking thing was the contrast in willingness to engage. Only a small number those who advocated clean sport and felt vehemently that cheats were damaging them were actually willing to say as much publicly. That’s understandable, not wanting to make a fuss or expose colleagues, perhaps trusting ‘the system’ to do it for them. On the flip side, there was resistance to taking part on an institutional level only from a few, cycling being one sport.

One post-script: a couple of years ago, I planned to repeat this study and started work on it. The resistance this time was almost sport-wide. Some sports made positive noises without actually getting to the point of agreeing to help circulate the forms. It was such a non-starter that we abandoned it after a few months of work. I commend British Swimming and badminton for getting on board immediately and having the confidence to let their athletes decide whether they could even be bothered to fill in a form or not (this time online to make it even easier). These are sports who feel they have nothing to hide, and nothing to fear from being open and at least having a conversation. The rest? Not so much.

But if there are any governing bodies out there who would like to get involved in a similar exercise again – please get in touch!

Some links to the 1998 Independent Drugs in Sport survey articles

Abuse widespread say sporting elite

Creatine: anatomy of a miracle substance

Authorities ‘failing British sport’

Verroken striving for zero defect

Cheats are getting away says Turner

Rugby must tackle widespread usage

Bowring tries to lift the stigma

The gear comes out of the locker rooms and onto the streets

The human cost of $1bn illegal market

Athletes in fear of the EPO era

Problem is here to stay says Baulch

Racing’s weighty problem fades

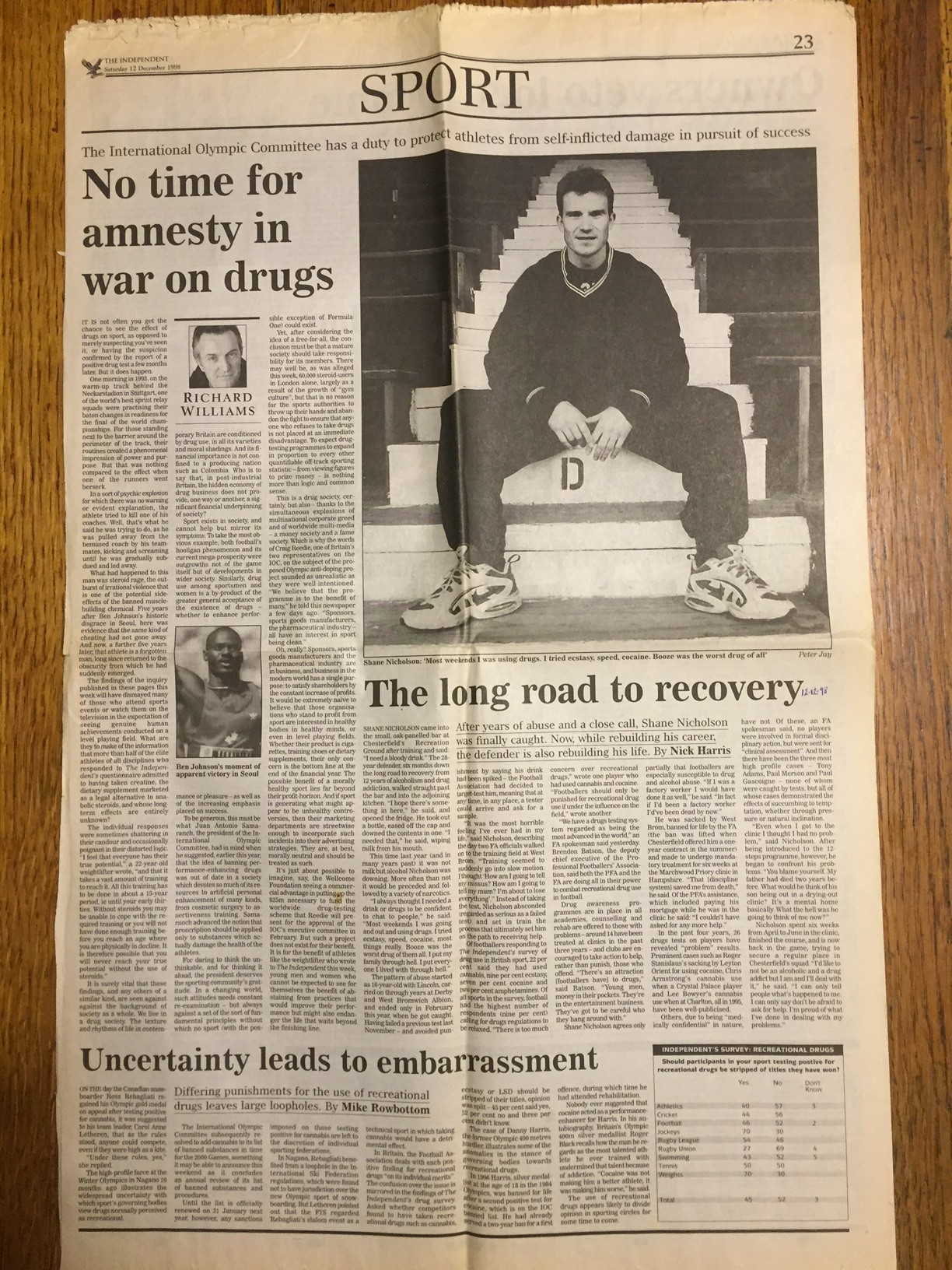

Uncertainty leads to embarrassment

No time for amnesty in war on drugs

.

And a 2016 story … EXPOSED: The story behind the story of Russia, doping and the IOC

Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter

.

See below for full original page scans from the Independent’s 1998 ‘Drugs in Sport’ series

.

.

.

.