*

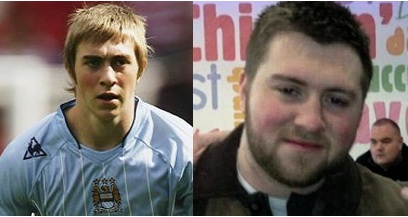

After the week in which we learned that Michael Johnson, the player hailed as the next Colin Bell, has been released by Manchester City, Ian Herbert asks why we don’t appreciate the mental challenge that football presents to some individuals who are lauded and loaded when they’re barely into their teens.

.

21 January 2013

One reading of the story of the player whom City have finally and reluctantly released is that he lacked the application to succeed, though the more telling one begins right back with his time in the Everton youth team, in the early years of the last decade.

It was then, when it became clear to those around him that he had a special talent, that the pressures, expectations and the pace of change began accelerating to a level which – in the opinions of those who have willed him to turn his career around in the past 12 months or so – left him hating the game and dreading his work, by the end.

Everton certainly seems like a good environment to flourish, though those around Johnson wanted to see him moving on and up. He was barely into his teens – a mere 14 years old, in fact – when he left the security of Merseyside for a brief spell at Feyenoord.

It didn’t work, though it was a mercy that this individual, with his complicated background, should then have alighted at City. The club didn’t have much money or infrastructure in those days but it did have Des Coffey, the education and welfare officer who has had an indelible effect on so many young men who have come from difficult backgrounds to City’s Platt Lane academy.

On the surface, there was certainly some braggadocio from Johnson. In one of their first conversations, Sven Goran Eriksson congratulated the midfielder – whom coaches loved because he always had so much time on the ball – for his part in the last nine matches of the 2006-07 season. To which, as Eriksson tells it, the Manchester-born player replied: “Yeah, I saved us [from relegation].”

But that was bluster – and not the real ‘Jonno.’

The player known in the club’s dressing room as FEC – ‘Future England Captain’ – and likened to Colin Bell after a number of Under-21 appearances in 2007, was universally liked.

It is safe to surmise that when, amid all the background expectations, the injuries began curtailing the expectations he carried, there was a heavy psychological toll.

The really damaging year was 2009. It brought frustrations of a kind which were not all physiological – like the undue emphasis, to his mind, that was placed on a summer bender at the end of the 2007-08 season which he thought had got him a bit of reputation.

But the setbacks from his attempt to return from an abdominal injury were what drained and punished him most.

Johnson returned to first-team training for Eriksson’s successor Mark Hughes during a winter break in Tenerife, and broke down almost immediately. He played superbly in a 3-0 win over Sunderland but was in pain soon afterwards. He finally managed 90 minutes in a reserves game against Blackburn Rovers in December, but sustained a serious, long-term knee injury which saw him stretchered from the Carrington training ground. One successful Carling Cup outing at Scunthorpe was sandwiched in between.

The words of manager Mark Hughes’s assistant Eddie Niedzwiecki from around that time are instructive. At times, Niedzwiecki said, “you could see it [the pain] etched in his features as he battled to get back on the pitch.”

During his periods of inactivity, Johnson was unable to control his weight. A photograph of the City squad taken on a tour of South Africa in the summer of 2009 which covered a wall of the media room at the Etihad Stadium revealed the way he had ballooned.

There were also drinking and gambling problems, though one of Hughes’ staff from the period believes it was the pressures and expectations of life as a top flight footballer that he was struggling to deal with.

“They’d been there right from the start when it was obvious that he had talent,” he says. “Mental health issues get scoffed at it in football and everyone points to the £35,000-a-week salary. But with a young player finds there’s so much money riding on his talent and can’t always cope with it.”

It is possible the psychological problems might actually have been a cause of the physical setbacks. These many injury setbacks had a habit of coming just as Johnson was back on the brink of the first team, again.

In this respect, the words of another former City coach last week felt very significant. “We loved Michael and rated him and wanted him in our team,” he said. “But he was never quite ready and always seemed to have a problem of some kind. It’s a hard thing to say, but often he would report to us as injured and our medical staff could find nothing actually wrong with him. No one ever doubted that he was in pain. We never thought he was making it up. But equally there were times when we just couldn’t really find anything physically wrong with him.”

If any club could save Johnson, then it was City – one of the most enlightened where the all-round welfare of their players is concerned, by virtue of the welfare unit, headed by Haydn Roberts, in which Coffey is still an important individual.

The club did indeed arrange for Johnson to see a sports psychologist on several occasions in a bid to help him focus his mind clearly on the challenging job of professional football. That City didn’t publicise their decision to terminate Johnson’s contract in December says much for the reservoir of affection for him there.

The very tangible sense that Johnson came to dread the job of work he had thought was his life’s calling restores to mind the writing of Paul Lake, whose description of how he dreaded the annual team photo is one of very many vivid aspects of his crumbling hopes, depicted in his I’m Not Really Here biography.

“Having to don a new Umbro kit, not even knowing if I was going to wear it that season was pure torture. And seeing my squad number dropping lower and lower down the list each year, from a coveted number 11 to a token number 32, didn’t do wonders for my self esteem either….”

Johnson’s acknowledgement last week that he has been attending the Priory Clinic for a number of years conjures the notion that his a case of addiction. But Johnson was clear. “I have been attending the Priory Clinic for a number of years now with regard to my mental health and would be grateful if I could now be left alone to live the rest of my life,” he said.

He is 24. It is a mere decade since those teenage Everton days when so much expectation was thrust on one so terribly young.

.

Ian Herbert is The Independent’s Northern Football Correspondent (see archive of his work here). Follow Herbie on Twitter here.

.

Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter

Sportingintelligence home page