*

In 1985, Steven Bridge, a lifelong fan of Charlton Athletic, was a mature student, age 31, living in Kent and studying theology in London. As part of his degree, he wrote an extended ‘Man in Society’ essay. As a football fan concerned by a blight on the beautiful game, he made hooliganism the subject of his piece, extensively researched and completed on 30 March 1985. The authorities, he felt, were overly concerned with crowd control while grossly dismissive of crowd safety. His paper explicitly warned of the dangers of caging fans at football grounds. It was sent to, and read by, senior government officials, the Football Association and the Football League, all of whom praised his diligence and insight. And then they completely ignored his findings. For the first time, below, Bridge’s correspondence is made public, as are his concerns that those culpable for the Hillsborough tragedy in 1989 are still evading responsibility.

.

20 May 2013

Next year it will be a quarter of a century since the Hillsborough disaster claimed the lives of 96 football fans who went to an FA Cup semi-final and never came home.

Nobody waking that morning and heading to see Liverpool play Nottingham Forest would have imagined the horrors that lay ahead, just as nobody afterwards could possibly have believed the quest for justice would take more than 24 years.

The screening of the BBC Panorama special on Monday evening – ‘Hillsborough – How They Buried The Truth’ – only goes to show the travesty that there remains so much concealment still to be exposed.

We all know now that complacent authorities, an inadequate ground and errant policing were the principle causes of the disaster, and that a generation-long cover-up has compounded the dreadful misery of all those affected.

What also haunts me still, as an ordinary football who hoped that warnings would be heeded years before Hillsborough, is that the authorities had been told this could happen – and they ignored it.

My own small role was an academic paper I finished in 1985, outlining my concern over crowd safety balanced against the measure of crowd control.

That paper, dated 30 March 1985, included this:

“As far as fences and cages are concerned, there are a number of drawbacks. Firstly, there is a view that police reaction to crowd control can be hampered by perimeter fencing. Secondly, there is always a real danger of crowd safety levels being reduced as the fences surrounding the ground would be a difficult obstacle to overcome in the event of a fire or a surge on the terraces. The way of escape on to the pitch is effectively ruled out by high fencing.”

Now if I had simply handed in my work at college and left it there, perhaps I would not feel as I do now.

But I sent it, on 13 April 1985, to the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher.

A few weeks later, on 11 May 1985, the Bradford fire left 56 people dead and at least 265 injured. A decrepit stadium and insufficient exits were partly to blame for the toll.

On the same day, a riot and a collapsed wall led to fatalities as Birmingham City played Leeds.

The events at Bradford and Birmingham were later examined in Justice Popplewell’s inquiry into safety at sports grounds.

Eighteen days after Bradford, on 29 May 1985, the Heysel Stadium disaster in Brussels claimed 39 lives and left 600 people injured.

Football clearly had a problem with hooligans but the football authorities, the police and governments were far from blameless.

Nobody from the Government replied to my letter to Mrs Thatcher.

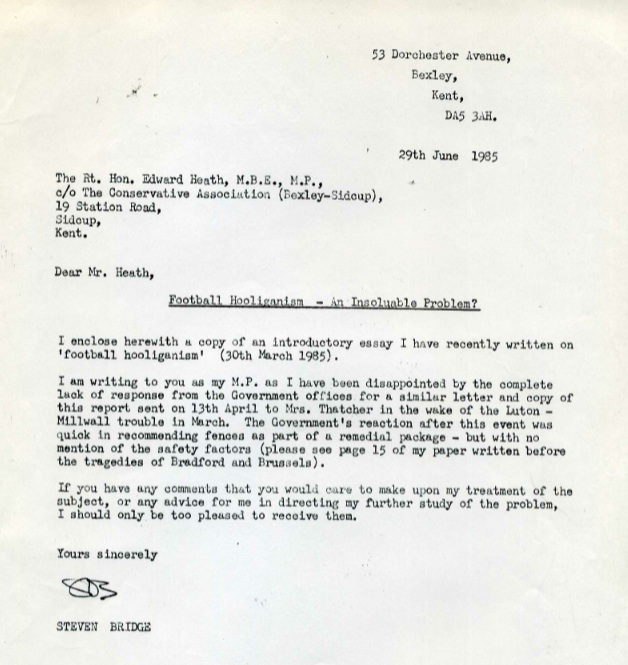

In the wake of Bradford and Brussels, I wrote instead to my MP, Sir Edward Heath, the former Prime Minister.

That letter is here:

Article continues below

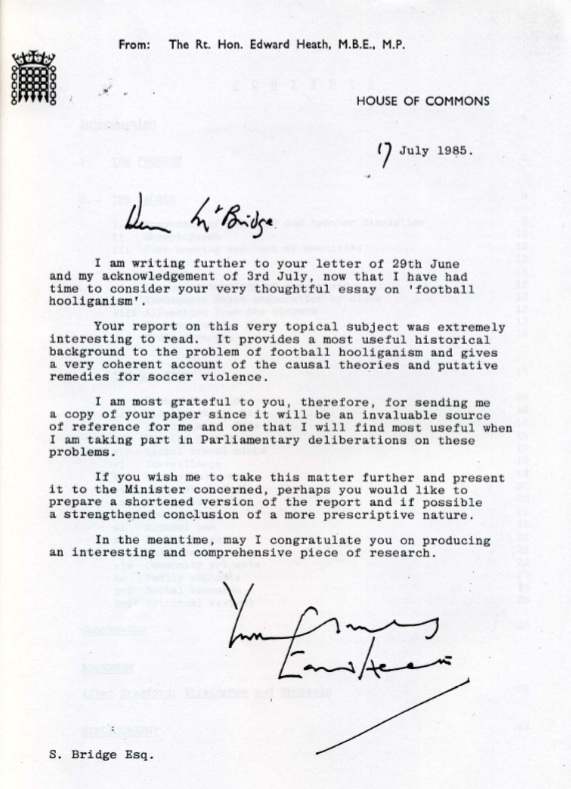

Ted Heath replied in July 1985 (below), saying my report gave ‘a very coherent account of the causal theories and putative remedies for soccer violence.’

My report had outlined that possible solutions to the problem of hooliganism had been overlooked, or not considered in sufficient detail. I suggested that family-friendly environments, actively fostered, could improve things. Watford at the time were promoting this way forward.

I highlighted the problem with fencing and cages.

If I, as a match-going fan, had the foresight to see this was a potentially serious problem, why did the authorities not?

Ted Heath wrote: “If you wish me to take this matter further and present it to the Minister concerned, perhaps you would like to prepare a shortened version of the report and if possible a strengthened conclusion of a more prescriptive nature.”

Article continues below

I did as Ted Heath suggested, sending him a tighter synopsis of my report and an addendum of specific measures. He passed it on to Richard Tracey, then the Environment and Sports Minister.

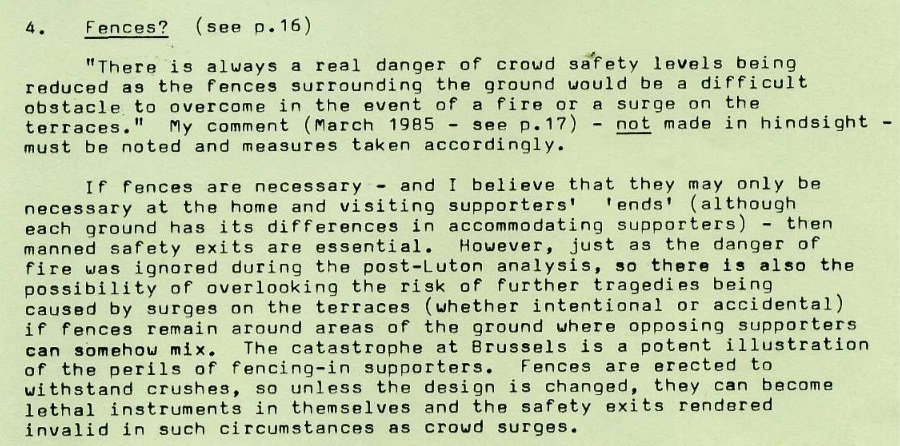

Here is what the addendum said on fencing, in reference to page 16 of the original report from March 1985:

Article continues below

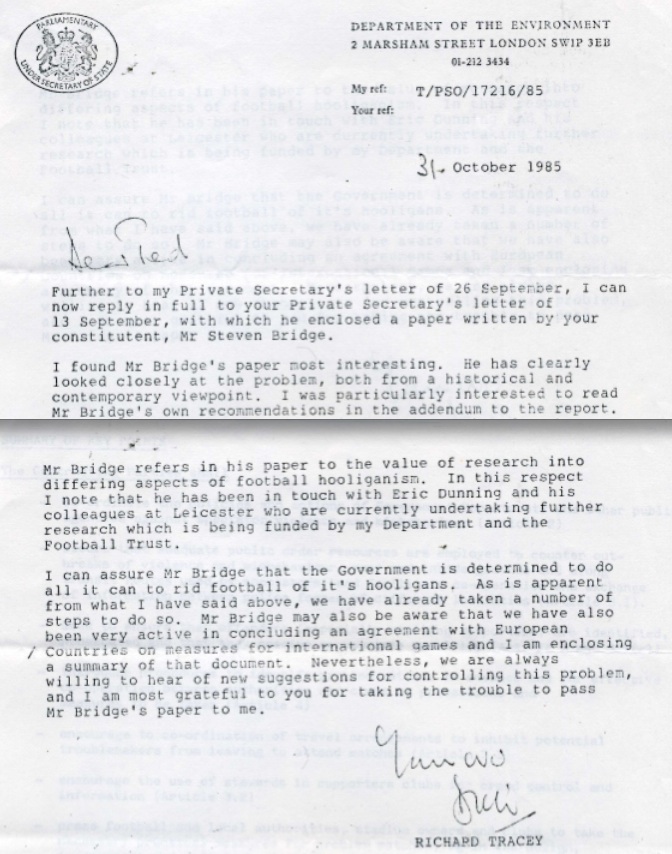

In a letter from the Sports Minister to Ted Heath dated 31 October 1985 (extract of first and last pages below) Richard Tracey said he had been “particularly interested to read Mr Bridge’s own recommendations in the addendum to the report.”

As well as fencing, my addendum made suggestions about all-ticket matches, CCTV and alcohol sales at games.

Richard Tracey outlined how the Government was looking at all these areas. But I felt he had missed the point, the point about fencing and cages, about basic safety.

It still very much seemed to me that their attitude was to exert control over fans who were all potential hooligans, not seek to protect people wanting simply to watch a football match.

Tracey’s letter said: “I can assure Mr Bridge that the Government is determined to do all it can to rid football of it’s [sic] hooligans … Nevertheless, we are always willing to hear of new suggestions for controlling this problem.”

Article continues below

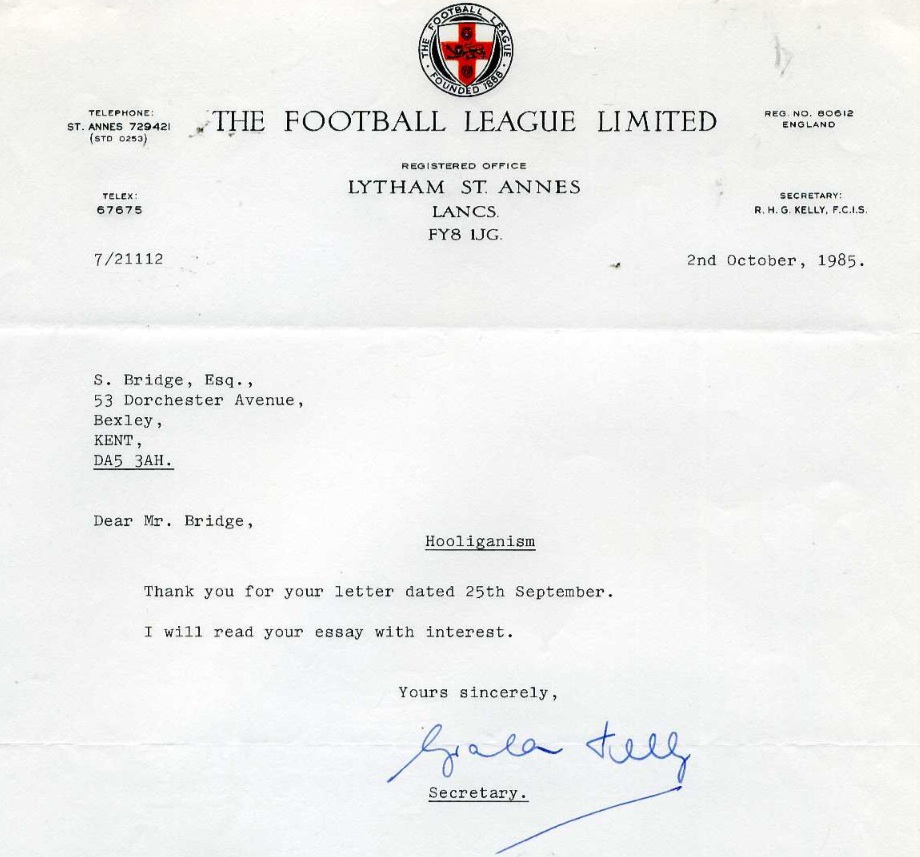

I also sent my report to the Football League, in September 1985, specifically to Graham Kelly, then the League’s secretary. All 92 clubs in the League had issues with crowd control and crowd safety, after all, and after the horrors of the Spring, surely the authorities wanted to ensure fan safety in the times ahead?

Mr Kelly’s reply is below, all fifteen words of it, including “I will read your essay with interest.”

I did not hear from him again. Kelly moved on from the League to the FA, where he was in charge at the time of the 1989 FA Cup semi-final at Hillsborough.

Article continues below

I am recalling all of this now, age 59 and still a football fan, because, in some way, I still feel haunted by Hillsborough; if not responsible then partly responsible for nothing being done to stop it.

If only I had persisted with my efforts to draw the attention of those in authority to my concerns over perimeter fencing and crowd safety being compromised, then what?

I was grateful that Ted Heath made a presentation of my paper to the Minister of Sport containing the heightened worry about perimeter fencing. I know I was disappointed with his reply and many times since Hillsborough I wish I had challenged the Government harder. I just do not think I was taken seriously by the powers that were.

I still feel ever so strongly that the focus on the police action/inaction on the day glosses over the evasion of the responsibility of the Government and the Football Association to ensure Hillsborough was a safe venue to stage an FA Cup semi-final in the first place.

I feel both of those institutions have a lot to answer for, along with the police, for the events that unfolded at Hillsborough.

It was a disaster waiting to happen.

It was predictable – and was predicted.

Yet the Government’s response under Mrs Thatcher in 1985 to hooliganism by Millwall supporters at Luton that focussed on crowd control to the detriment crowd safety was indicative as well as inadequate.

I also made a submission along the lines above to the Popplewell Inquiry on 25 September 1985, after the events of Bradford, Birmingham and Brussels.

I do feel the Government of the day in 1985 has a lot to answer for and I respectfully wonder if current politicians are overlooking this.

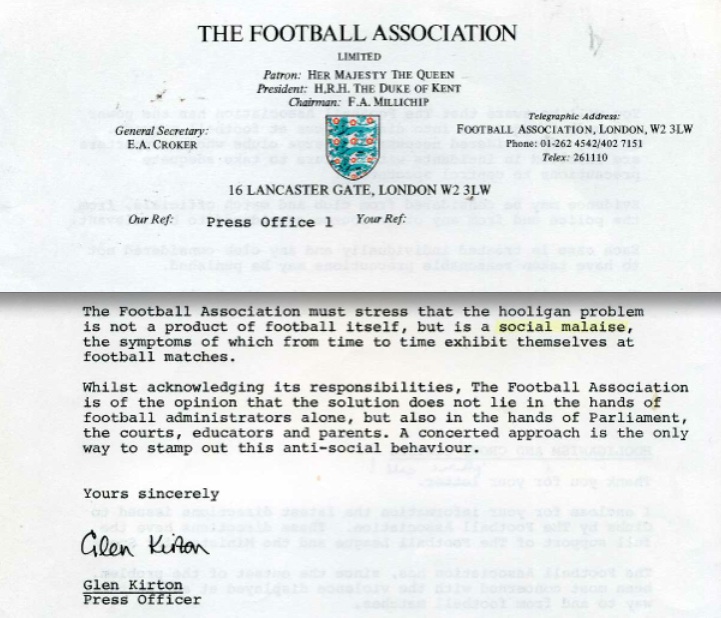

As for the Football Association, I believe they have neatly sidestepped their responsibility and culpability.

Of course I was not an expert on crowd safety but as a fan – an ordinary fan on the crowded terraces of the era – I was aware of the inherent dangers concerning perimeter fencing – a significant factor in the cause of death at Hillsborough.

I also sent my 1985 report to the FA.

I will finish this with their response, the header and final two paragraphs reproduced below.

The prevailing view was clear: football fans were there to be dealt with, not taken care of.

One day soon, I fervently hope, there will be justice for the 96.