By Nick Harris

24 June 2013

As tennis’s most prestigious grass court tournament begins at Wimbledon today, the presence of one particular American qualifier in the men’s singles draw highlights the sport’s deeply complex relationship with match-fixing, doping and whistle-blowing.

Wayne Odesnik, 27, is the world No107 and has previously been ranked inside the world’s top 100.

Wayne Odesnik, 27, is the world No107 and has previously been ranked inside the world’s top 100.

An extensive investigation by Sportingintelligence has unearthed extraordinary new information about how Odesnik did a deal to allow him to return early from a drugs conviction and after being investigated for involvement in a suspicious match at Wimbledon.

The findings raise serious questions over the lack of transparency in the way tennis tackles fixing and doping – and whether fans should have faith in the matches they are watching.

In 2009, Odesnik was investigated by the Tennis Integrity Unit (TIU) following a first-round match at Wimbledon when around £1m was wagered on him to lose to Austria’s Jurgen Melzer. Hundreds of thousands of pounds were gambled specifically on the 3-0 score line. Odesnik duly lost 3-0. The TIU has never confirmed it investigated Odesnik but multiple sources have now confirmed it to Sportingintelligence, and official documents, of which this website has knowledge, prove it.

In early 2010, Australian customs officials found Odesnik in possession of human growth hormone (HGH), a banned performance-enhancing anabolic agent, and other ‘medical paraphernalia’ including syringes. He was fined by the Australian courts, then charged by the tennis authorities for a violation of the anti-doping rules and banned from playing for two years.

The same year, 2010, he cut a deal with tennis’s global governing body, the ITF, to turn whistle-blower on drugs and match-fixing. It was widely and erroneously reported his ban was shortened for information only on drugs. Sources say the deal was done was thrashed out by Odesnik and lawyers, including a lawyer working for the ITF, Jonathan Taylor. The head of the TIU at the time, Jeff Rees, later met Odesnik in Miami to continue mining for information.

At the end of 2010, the ITF confirmed Odesnik would be free to return to competition that month. Given that he had played until April 2010, and was free to return in December, he was actually out of action for nine months of his two-year ban.

In January 2011, some of Odesnik’s whistle-blowing information was used as the basis for corruption charges laid against an Austrian player, Daniel Kollerer. In written and oral testimony in a case that saw Kollerer banned for life in 2011, Odesnik described how the Kollerer case was just “a small part” of the whistle-blowing that got his own ban halved, more of which later.

Astonishingly, Odesnik was described in the secret Kollerer ruling as a “wholly unreliable witness” and yet neither the TIU nor ITF can explain how his whistle-blower’s amnesty remained in place. Both bodies declined to anwer questions relating to fixing, doping and whistle-blowing.

Sources in early 2011 told Sportingintelligence that Odesnik could always have the suspended year of his ban re-imposed at a later date if he turned out to be an unreliable whistle-blower or was ever proved to be involved in other doping or fixing himself.

Odesnik spent most of 2011 trying to move back up the rankings, post-ban. He played in 23 tournaments, mostly on the Challenger circuit, taking in events in the USA, Colombia, Panama, Slovakia, Italy, Germany, Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Ecuador. He was gathering information along the way to pass to the authorities – but then so do quite a lot of other players, sources say.

The TIU’s staff spend much of the year traveling to events, interviewing suspects, persuading players to pass on information about others. It is unknown how many suspected fixes they investigate each year: no details are made public. Charges are not made public, only outcomes with no specific details. Hearings are held in secret.

It is known the TIU speak to dozens of players each year, perhaps many more, seeking information on ‘suspicious’ events. Sportingintelligence estimates that least 14 players in this year’s men’s singles draw alone at Wimbledon have spoken to the TIU in relation to suspicious matches. Not all of them will be implicated in fixing but it is impossible to know.

The TIU is funded by the “tennis family” – the ITF, ATP, WTA and the Slams – and operates a “no comment” policy on all operational matters. Thus it is not known how many deals the ITF and / or TIU have done with players to allow them to continue playing after breaking tennis rules, in exchange for information.

One senior betting integrity expert recently voiced concerns that tennis is clamping down on minor, obscure players while letting ‘bigger’ stars off the hook, publicly at least. “There were certainly elements within the ruling bodies, who fund the TIU, that wanted stuff swept under the carpet,” the integrity expert said. “But to do the job to the full extent, you need to tackle the higher profile people involved and not just the lesser players. If you don’t want a problem [with bigger players], don’t look for it. And if you want to look for it, be aware that it won’t smell sweet.”

By summer last year, Odesnik was back at Wimbledon, playing in the main draw. He was something of a pariah because of the perception among fellow professionals that he was a drug cheat who had got off lightly for informing on others. Odesnik’s compatriots Andy Roddick and James Blake were among those who wanted him banned, while Andy Murray, who alluded to Odesnik as a ‘snitch’, said: ‘You want to make sure that people who are fined and suspended aren’t let off because they are telling on other players.’

Murray’s point, misconstrued in some quarters, was not that there is anything wrong with the authorities pursuing drug cheats by whatever means, but that leniency should not be offered to cheats.

In this corresponding week a year ago, Odesnik sat in Wimbledon’s press conference room and unequivocally denied being a “snitch”.

He said: “I think one thing I would like each and every single one of you to jot this down in capital letters: I would 100 percent never say anything bad about a player or do something that I was a spy or something of that sort. That is utterly 100 percent false. I don’t know where you guys started this rumor or where you heard it from, but I think that needs to be clarified.”

This was not true: Odesnik had entered a whistle-blowing pact and had been feeding the authorities all kinds of information.

This he confirmed in his own words as he gave video link evidence from Florida in April 2011 to a corruption hearing in Britain. Here, Odesnik is being quizzed on his whistle-blowing:

Q: “Did you give them [the authorities] information about anyone apart from Mr Kollerer?”

Odesnik: “I had given information on a few other players.”

Q: “About what subjects? Match fixing, doping or what?”

Odesnik: “I had given information on both matters.”

Q: “What proportion was about Mr Kollerer? Just a little part or was it mainly him?”

Odesnik: “He was a small part of it.”

Q: “So the reduction that you got from two years to one year was not just in return for information about Mr Kollerer?”

Odesnik: “Correct. It was not just about Kollerer.”

What is not known are the precise terms of Odesnik’s ban amnesty.

The apparent randomness of the system is highlighted by the fact that even as he prepares to play at Wimbledon tomorrow, when the least he can expect is a £23,000 cheque for being a first-round loser, he is under scrutiny again because his name appears multiple times in the hand-written records of a Miami clinic at the centre of a huge developing doping scandal in American sport.

The clinic’s founder, Tony Bosch, is being investigated for allegedly supplying banned drugs to scores of big-name stars, mainly from baseball and boxing. Odesnik’s name appears in the records in 2009, 2010 and 2011.

Odesnik has denied ever being a client of Bosch and has said: “I have never purchased HGH, nor any other illegal/banned substances from any person.”

His US-based lawyer, Chris Lyons, says Odesnik declines to comment further.

Stuart Miller, the anti-doping manager for the ITF, said the ITF is following up new information on Odesnik and an ITF spokesman says: “We are not in a position to make any further comment.”

The Daniel Kollerer case, to cite just one example in detail, throws some light on the extent to which players believe corruption is happening, and the secrecy under which tennis operates in its ‘trials’, punishments and deals.

Kollerer, an Austrian, long had a ‘bad boy’ image, and he was notorious on the circuit for outrageous on-court antics. He first fell foul of the anti-corruption unit when he was prosecuted because his manager did a partnership deal with a betting firm to promote a bookmaking firm via Kollerer’s website. There was no suggestion he was fixing.

The fixing charges came in 2011, five of them, with three eventually upheld and later ratified by the Court for Arbitration in Sport, which ruled tennis was within its rights to have a low evidence threshold in disciplinary matters.

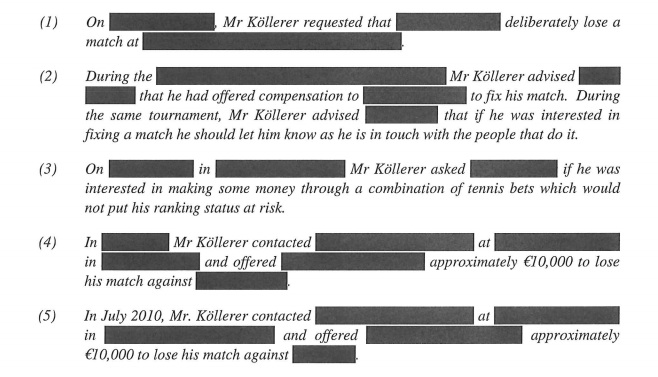

What has never been revealed before now is what those charges were, or the evidence with which they were ‘proved’ or thrown out. The CAS ruling (linked here) provides only a redacted version of the charges. These are the redacted charges:

Story continues below, with actual charges and evidence

.

The details of actual charges were (additional notes in blue):

1) In October 2009, that Kollerer requested that former world No13 (and current world No37) Jarkko Nieminen deliberately lose their meeting that week in Vienna. Nieminen lost the match in question but insisted he lost it fairly and did not throw it. He reported Kollerer’s ‘approach’ after his defeat, days after the approach.

2) During the same tournament in Vienna, Wayne Odesnik said Nieminen had been offered money by Kollerer to fix that Kollerer-Nieminen match, and that Kollerer had told Odesnik that if he was interested in fixing matches himself, then he, Kollerer, was the man to speak to. Odesnik was not believed.

3) That Kollerer asked a fellow Austrian player, Martin Slanar, in June 2010, if he was interested in making cash out of fixing. Slanar was not believed.

4) and 5) That Kollerer called a Spanish player he did not know well, Daniel Munoz de la Nava (the current world No146), on two occasions on consecutive weeks in June and July 2010 and asked him if he was interested in making money from throwing matches. Munoz de la Nava was believed.

Without going into the minutiae of the charges and evidence, charges 1, 4 and 5 were upheld, while 2 and 3 were dismissed because the ‘judge’ in the case, Tim Kerr, QC, did not think Odesnik and Slanar were credible but thought Nieminen and Munoz de la Nava were more credible than Kollerer, even in the absence of any ‘physical’ evidence.

There was no suggestion at any stage that Kollerer had actually managed to fix any of the matches in question. There was no betting evidence, no phone record evidence and Kerr stressed in his ruling that if he had not used the lowest possible evidence threshold (which is dictated by tennis rules should be used) he would have found it hard to convict Kollerer on any of the charges. As it transpired, Kollerer was banned for life.

Technically speaking, several of the witnesses in the Kollerer case, and others in other cases, had broken tennis rules by knowing about fixing allegations and failing to report them. Deals have been done to not prosecute in exchange for information.

The sheer scale of the information gathering, whistle-blowing, deal-making and prosecution process is hinted at by the cast in the Kollerer case. At his ‘trial’ he was accompanied by his own lawyer, Herbert Heigl and manager, Manfred Narayka. Jeff Rees was there as the head of the TIU, as well as his chief investigator, Nigel Willerton (who has since taken over as the head of the TIU). Bill Babcock of the Slams was there, and Gayle David Bradshaw of the ATP, as well as Stuart Miller and an assortment of solicitors and counsel.

Witnesses in person or via video included Munoz De La Nava, Austrian players Martin Fischer, Philipp Oswald, Andreas Haider-Maurer and Slanar, Jarkko Nieminen and his mum, Leena. This case and others also cited names of players implicated in suspicious matches.

Slanar and Odesnik, two players labelled as unreliable, were also the two players in the Kollerer case who said they were not surprised at frequent suggestions of wrong-doing in tennis. Slanar said: “These stories [allegations of corruption in tennis] I hear almost every day or two, not just about betting but that a player did this or that.”

Odesnik was quizzed on why he was not shocked that one player would openly ask him whether another would be open to fixing.

Q: “Isn’t it quite shocking for a player to ask another player about would so and so be willing to fix a match?”

Odesnik: “It is not the strangest thing I’ve heard on tour.”

Q: “Is it not?”

Odesnik: “No.”

Wayne Odesnik is due to play his first-round match in the men’s singles on Tuesday against Jimmy Wang of Taiwan.

.

More stories on this site mentioning fixing in sport / doping / tennis

REVEALED: The best paid teams in global sport

From £200m Messi to £20m Lukaku: Europe’s 60 most valuable players this summer