*

Boxing’s 24-hour weigh-in lets fighters “boil down” for weigh-in day then pile the weight back on before the fight. It encourages extreme dehydration, leaving those who do it susceptible to heat stroke, heart failure, increased risk of brain damage and death. Little has been done adequately to investigate the subject, which is one reason Barry J Whyte took it upon himself to do so. The result is ‘Making the Weight: Boxing’s Lethal Secret‘, a compelling piece of long-form investigative journalism, on sale now. It focuses primarily on the consequences of a fight between Joey Gamache and Arturo Gatti at Madison Square Garden in February 2000. Gatti weighed in at 139 pounds and fought at 160. It wasn’t an even fight (see video at foot of this piece) – and all manner of lessons still remain to be learned.

.

24 June 2013

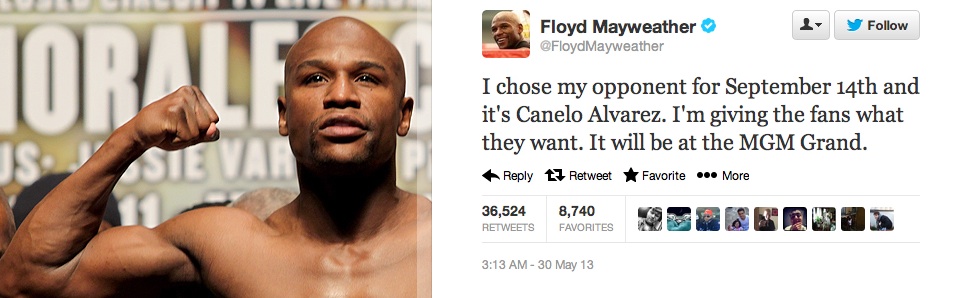

Boxing blogs have been abuzz since Floyd Mayweather agreed to a catchweight of 152 pounds for his upcoming fight with Saul ‘Canelo’ Alvarez. Worse still, for Money fans, he’s enforced no rehydration limit on Canelo.

A sample of comments illuminates what has been viewed as the big issue around Mayweather’s latest challenge.

“Mayweather really blew it by not insisting that a clause be in the contract because he’ll likely come into the fight weighing no more than 150 at the most and more likely around 146 or 147.”

“If Canelo rehydrates to 170-172, he’ll have a considerable weight advantage over Mayweather. Indeed, Canelo will have a weight advantage that most fighters would die for.”

“I’m respecting Mayweather a ton for letting Canelo take the fight without a clause because the chances are Mayweather is going to be out-weighed by 26-30 pounds for this fight.”

.

The truth is, Mayweather – who rarely puts himself in a position where he has to dehydrate – knows that the more Canelo rehydrates, the better. A fighter who balloons 15 to 20 pounds has just come off a gruelling dehydration session. And while the water has gone back into his body, it has not replenished the muscles and cells and organs – including the precious, vulnerable brain. That takes days more.

So while Mayweather cedes advantages in age and weight, he has given Canelo a huge incentive to exhaust himself before the fight. Canelo is likely to run himself down even further chasing Mayweather and to eventually expose himself to the older fighter’s counterpunching style.

That’s all fascinating from a tactical, boxing perspective – and very astute by Mayweather – but, neurologically, Canelo is in serious peril. A dehydrated brain, no matter how much water he loads into his system after the weigh-in, will be smaller in volume and will have greater distance to move within his skull.

While the distance is just millimetres, it’s additional millimetres across which the moving brain – directly after a punch, for example – can pick up force and crash into the inside of the skull. This is not insignificant. As we learn more about how the brain reacts to impact, it becomes clear that it’s not the big, shocking impact that causes the damage anymore, but the low-level, repetitive impact – which is virtually the definition of boxing.

Moreover, a boxer who has been dehydrating will be physically depleted and so less well able to defend himself; he will take more punches than normal, further exposing him to an accumulation of brain trauma.

This is not a problem isolated to Mayweather versus Canelo. Today, virtually all boxers engage in this dangerous dehydration to some degree. And few boxers talk about the process in detail.

While I was investigating the process and the risks of long-term brain to which boxers expose themselves, I spoke to one boxer who agreed to explain the process in detail, but refused to let his name be used.

In the extract below, he is referred to as Tony:

A few years ago, Tony found himself in a difficult situation before one of his title defences. With 20 hours to go to his official weigh-in, he was 20 pounds too heavy. If he got caught cutting so much weight he risked losing his title and his licence to box. If he didn’t lose the weight, he’d lose his title without a fight.

He chose to lose the weight.

While most boxers limit their intake of water and exercise in sweat suits, Tony resorted to the full body sauna, inside of which he wore layers of clothes with a sweat suit, three t-shirts, long johns and thermal bottoms to soak up the sweat. And his head, though outside the sauna, was covered with a wool cap to keep it sweating. Like all boxers, his goal was to remove all that so-called water weight in the hope that it could be replaced in the 24 hours before the fight.

“Most people don’t know what it’s like to spend so much time in a sauna,” he says. “It starts to affect your mood. You start getting really agitated. You start panicking because you’re so hot. It isn’t so much claustrophobia as panic. You’re overheating and all your body’s natural defences are telling you to get out. I stayed in for 40 minutes to start, then came out for ten, then went back in for 20, then ten, then five, and it wasn’t long before I could only stand a couple of minutes at a time.”

As he became more dehydrated, and more fluids left his body and brain, Tony’s mind began to drift. He would be in that semi-dream state for the next few days, all through the fight, and for days afterwards.

That night in the sauna, having eaten nothing that day and drunk no water, Tony shed 11.5 pounds. It was already more weight than he had ever lost for a fight and he was far from finished. “To keep going, I was trying to convince myself that it wasn’t too bad, that I was handling it. But the truth was, I couldn’t even drive myself home. I just didn’t feel confident at the wheel.”

On the morning of the weigh-in, Tony had 9.5 pounds left to shift and five hours in which to do it. He’d had his last protein shake at 3pm the previous day, with just 500 millilitres of rehydration fluid containing precious salts and minerals since then. His mouth was dry and he felt completely sapped. All he could manage was ten minutes in the sauna followed by ten minutes lying on the couch, exhausted, with a wet towel over his face to promote more sweating.

“By that stage, I was really agitated, really fretting. And I could tell from [other people’s] faces I didn’t look well,” he says. “I had a horrible cramp in my solar plexus, like severe hunger pains.”

By 11.30am, he had boiled down to his last pound but it was taking hours to evaporate. After yet another ten-minute spell in the sauna, with his mind beginning to phase in and out of focus, he weighed himself. He was 0.1 pounds overweight. Close enough, he thought. “I was just happy to be out of the sauna.”

In the videos of the weigh-in, the skin on Tony’s normally round face is drawn tight around his cheekbones. His forehead and the orbital bones of his eyes are shockingly prominent. His eyes are circled with dark rings and his face is pasty and drawn. “I looked like I was dying of cancer. And I was in pain. It hurt to breathe. My throat was so dry that if I inhaled through my nose, it would actually hurt me.”

Eyes vacant, Tony steps gingerly up to be weighed. The scale is no more than four inches off the ground, but even at that small height his movements are not coordinated. He gives the crowd a wan smile and curls his biceps, but he does not look fully there. His opponent steps confidently on to the scales, posing for the crowd, smiling, flexing his muscles.

On the morning of the fight, Tony awoke with a huge headache centred behind his eyes, unable to focus and weighing 21.5 pounds more than the night before, just from drinking water. But he was not even close to being rehydrated and the doubts were beginning to creep in. “All I could think was, ‘I hope you can do this. I hope you can pull it off.’”

“It wasn’t self-pity. I knew I wasn’t capable of going 12 rounds. Even if all I did was chase him around the ring, without throwing even one punch, I was going to run out of steam pretty quickly. Everything had gone into making the weight.

“Usually when you’re knocked out you don’t know it, you don’t see it. I see this one,” he says of the punch that knocks him out, “but I can’t do anything about it. I didn’t get knocked out. He lets me walk on to the punch,” he says. “I get dizzy, all my equilibrium goes. I get wobbly. I fall sideways into the ropes.”

As he walked out of the ring that night Tony had only dehydration on his mind: “On my way back to the dressing room I was thinking, ‘Fucking hell, that’s what you get.’”

Barry J Whyte is the author of Making the Weight: Boxing’s Lethal Secret, available for download on the digital-only sports imprint 90 Minutes from www.backpageporess.co.uk, exclusively through the Kindle store for Kindle devices or for the Kindle app. Follow Barry J Whyte on Twitter

.

REVEALED: The best paid teams in global sport

From £200m Messi to £20m Lukaku: Europe’s 60 most valuable players this summer

Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter

.