*

Major League Soccer Commissioner Don Garber recently announced plans to extend his organisation’s geographic reach by adding five new franchises by 2020. The new entrants will boost MLS to 24 teams – a haunting reminder for older American fans who witnessed the North American Soccer League’s swift demise after peaking at 24 franchises in the late 1970s. But, as Ian Thomson writes, it’s not as if the NASL or its predecessors, including the ‘one year wonder’ of the United Soccer Association, were without their thrills and spills.

23 September 2013

Factors underpinning soccer’s current growth in the United States bear little resemblance to the balmy, barmy days of Pelé and the New York Cosmos.

Americans bought more tickets for the FIFA 2010 World Cup in South Africa than fans from any other country except the hosts.

Jurgen Klinsmann has guided the Stars and Stripes to a seventh consecutive World Cup in Brazil next summer, and only Klinsmann’s native Germany boasts more registered players than the U.S.

Soccer is no longer the foreign pastime that it was in 1967 when multi-millionaire sports promoters first launched a new continent-wide professional league, the United Soccer Association (U.S.A).

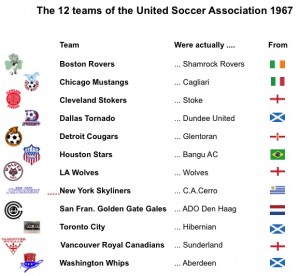

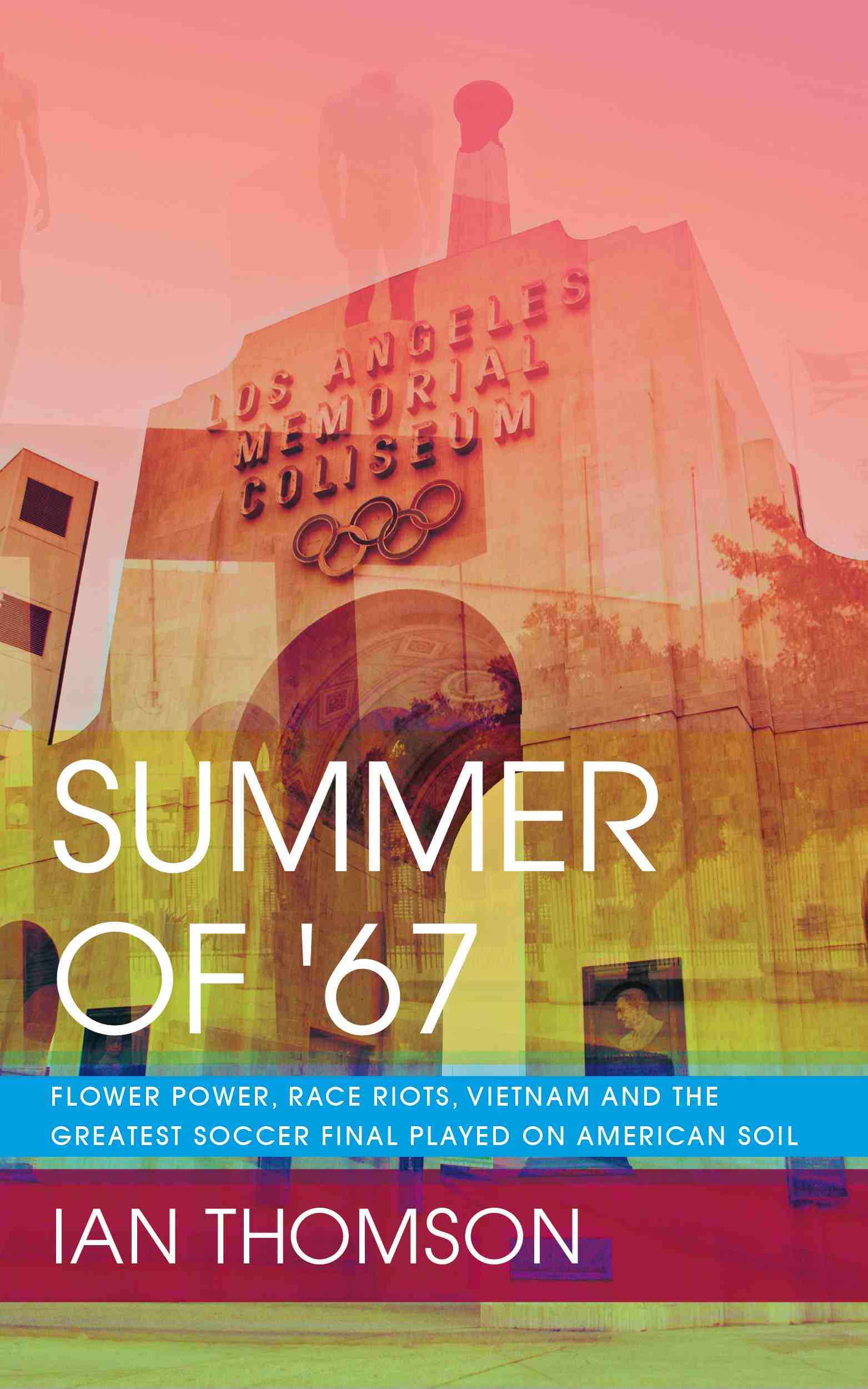

As chronicled in my new book, ‘Summer Of ’67: Flower Power, Race Riots, Vietnam and the Greatest Soccer Final Played on American Soil,’ the U.S.A comprised 12 teams from the LA Wolves and the San Francisco Golden Gate Gales in the west to the Boston Rovers, New York Skyliners and Washington Whips on the eastern seaboard.

Then there were the Chicago Mustangs, Cleveland Stokers, Dallas Tornado, Detroit Cougars, Houston Stars, Toronto City and Vancouver Royal Canadians.

Except these teams weren’t quite what they seemed. They were, for one summer only from late May to mid-Jul 1967, the alter egos of clubs from elsewhere, mostly Britain, including Stoke, Sunderland and Wolves, and Dundee United, Hibernian and Aberdeen. (Full list right).

And in an extraordinary denouement that determined North America’s first soccer champions on 14 July 1967 at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, the Wolves and the Whips (or Wolves and Aberdeen) played out the greatest final ever played on American soil.

There were 11 goals, two hat-tricks, three penalty kicks and last-minute equalisers in normal and extra-time. There was an early sending off, countless punch-ups and a heartbreaking golden own goal in sudden-death overtime to decide, eventually, the outcome.

The highlights are in this video, which has a ‘scratchy’ picture early on but clears after the first minute or so:

.

Article continues below

.

Jack Kent Cooke, a cable television magnate who owned the Los Angeles Lakers of the NBA and a stake in the NFL’s Washington Redskins, had secured England’s Wolverhampton Wanderers to represent his Los Angeles Wolves franchise. After his Wolves had won, he told a crowd of almost 18,000: “There isn’t a writer in Hollywood, there never has been one, who could have written a script for the game tonight.

“Next year and the year after and all the years to come, we’re going to be proudly privileged to bring you wonderful fans major league soccer here in Los Angeles.”

Professional sport had blossomed in the post-war years as rising disposable income allied to advances in television and transportation fostered a generation of heroes on baseball diamonds, basketball courts and football fields. America’s traditional sports expanded beyond their northeastern strongholds to California, Texas and elsewhere in the south and west.

Lamar Hunt, the son and heir of Dallas oil tycoon Haroldson Lafayette Hunt, sparked American football’s expansion (that’s gridiron, not soccer) after establishing the American Football League when his attempts to buy an NFL franchise were rebuffed.

A $36 million contract with broadcaster ABC allowed Hunt’s AFL to attract top players and eventually force the rival leagues to merge in June 1966. One month later, the first stand-alone broadcast of a soccer game was shown on U.S. television when NBC aired the FIFA World Cup Final between England and West Germany.

“We had the biggest television audience in United States sports history for the Super Bowl game, 65 million viewers,” said Hunt after the first AFL-NFL championship game in January 1967. “But do you know how many people all over the world watched the World Cup soccer matches? Four hundred million.”

The potential for the world’s most popular sport to bring in television dollars was irresistible. Two rival ownership groups announced plans to begin soccer leagues in 1967. Hunt’s Dallas Tornado joined the United Soccer Association, which circumvented a lack of local talent by importing 12 teams from Europe and South America to compete in its inaugural two-month summer tournament.

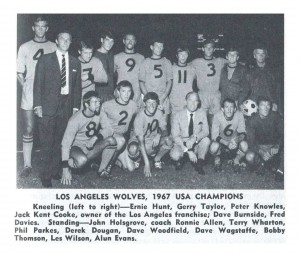

Cooke turned England’s Wolves into his Los Angeles Wolves franchise (winning team from 1967 pictured left). Cagliari of Italy played under the guise of the Chicago Mustangs side run by Arthur Allyn Jr., the owner of the city’s White Sox baseball team. Hunt welcomed Scotland’s Dundee United, including teenage defender and future coaching legend Walter Smith, to Texas.

Cooke turned England’s Wolves into his Los Angeles Wolves franchise (winning team from 1967 pictured left). Cagliari of Italy played under the guise of the Chicago Mustangs side run by Arthur Allyn Jr., the owner of the city’s White Sox baseball team. Hunt welcomed Scotland’s Dundee United, including teenage defender and future coaching legend Walter Smith, to Texas.

This was an era when soccer players were largely working class lads from industrial towns earning average wages. They lived in standard houses and joined the regular workforce after their careers had ended. Many of the players had barely strayed from their home countries. Former Manchester United captain Martin Buchan, who represented the Washington Whips with his hometown club Aberdeen, had never even been on a family holiday in Scotland.

Yet here they were jetting around North America, checking into grand hotels like Toronto’s Royal York and the Washington Hilton, rubbing shoulders with rock and roll stars like Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Stevie Wonder and being feted by their affluent hosts.

Cooke’s prediction about the future domination of the United Soccer Association proved premature. The U.S.A merged with its rival, the National Professional Soccer League, to form the North American Soccer League (NASL) that stuttered through the early 1970s before its dramatic decade of boom and bust.

The measured growth of MLS and soccer’s entrenched popularity suggest that history is not about to repeat itself.

Follow Ian Thomson on Twitter @SoccerObserver or visit www.thesoccerobserver.com

.