*

EUROPE’S major leagues delivered a string of titles by procession in Spring 2013 as a group of the biggest, richest clubs across the continent romped to runaway victories. Most leagues have always had one or two dominant clubs but is there something else afoot now? And what if anything does that say about the state of European football? This piece first appeared in the debut – and current – issue of Eight by Eight (cover below), available on order now.

5 November 2013

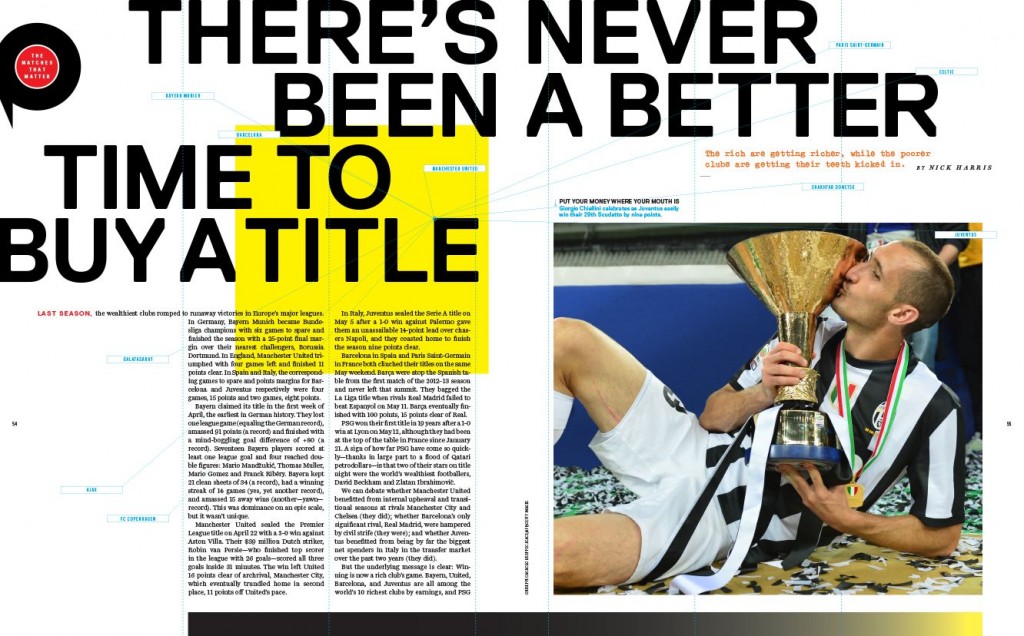

Last season, the wealthiest clubs romped to runaway victories in Europe’s major leagues. In Germany, Bayern Munich became Bundesliga champions with six games to spare and finished the season with a 25-point final margin over their nearest challengers, Borussia Dortmund. In England, Manchester United triumphed with four games left and finished 11 points clear. In Spain and Italy, the corresponding games to spare and points margins for Barcelona and Juventus respectively were four games, 15 points and two games, eight points.

Bayern claimed their title in the first week of April, the earliest in German history. They lost one league game (equaling the German record), amassed 91 points (a record) and finished with a mind-boggling goal difference of +80 (a record). Seventeen Bayern players scored at least one league goal and four reached double figures: Mario Mandžukic, Thomas Muller, Mario Gomez and Franck Ribéry. Bayern kept 21 clean sheets of 34 (a record), had a winning streak of 14 games (yes, yet another record), and amassed 15 away wins (another—yawn—record). This was dominance on an epic scale, but it wasn’t unique.

Manchester United sealed the Premier League title on April 22 with a 3-0 win against Aston Villa. Their $39 million Dutch striker, Robin van Persie—who finished top scorer in the league with 26 goals—scored all three goals inside 31 minutes. The win left United 16 points clear of archrivals, Manchester City, who eventually trundled home in second place, 11 points off United’s pace.

In Italy, Juventus sealed the Serie A title on May 5 after a 1-0 win against Palermo gave them an unassailable 14-point lead over chasers Napoli, and they coasted home to finish the season nine points clear.

Barcelona in Spain and Paris Saint-Germain in France both clinched their titles on the same May weekend. Barça were atop the Spanish table from the first match of the 2012–13 season and never left that summit. They bagged the La Liga title when rivals Real Madrid failed to beat Espanyol on May 11. Barça eventually finished with 100 points, 15 points clear of Real. PSG won their first title in 19 years after a 1-0 win at Lyon on May 12, although they had been at the top of the table in France since January 21. A sign of how far PSG have come so quickly—thanks in large part to a flood of Qatari petrodollars—is that two of their stars on title night were the world’s wealthiest footballers, David Beckham and Zlatan Ibrahimovic.

We can debate whether Manchester United benefitted from internal upheaval and transitional seasons at rivals Manchester City and Chelsea (they did); whether Barcelona’s only significant rivals, Real Madrid, were hampered by civil strife (they were); and whether Juventus benefitted from being by far the biggest net spenders in Italy in the transfer market over the past two years (they did).

But the underlying message is clear: Winning is now a rich club’s game. Bayern, United, Barcelona, and Juventus are all among the world’s 10 richest clubs by earnings, and PSG is owned by Qatar Sports Investments, a subsidiary of a Qatari sovereign wealth fund with tens of billions of dollars at its disposal.

Competitive balance in the elite leagues of Europe is worsening. This is proved by data released in June by the academic team at the highly respected CIES Football Observatory in Switzerland. “At ‘Big 5’ league level, the spread in points in 2012–13 was higher than the average measured during the last decade,” it found. This is related to greater financial disparities: Revenues of top clubs rose more than those of middle- and bottom-ranked ones.

“Without new regulatory mechanisms to improve income distribution, competitive balance will be further jeopardised through the transformation of top level clubs into global brands, [through] their regular participation in the increasingly lucrative Champions League and investments made by wealthy owners.”

It is ironic that income from the Champions League is a reason for the growing disparity between the elite and the rest. The Champions League, of course, is the flagship club tournament of European football’s governing body, Uefa, which is simultaneously in the process of implementing its sensible new Financial Fair Play (FFP) rules. One of the aims of FFP is “to encourage clubs to compete within their revenues.”

Yet Uefa has helped create a community of haves and have-nots, via the billions of euros of Champions League prize money over the past decade that has gone primarily to the same group of clubs who turn up in the Champions League more often than not. “Competing” and “within their revenues” are becoming mutually exclusive terms for many.

The ‘“big” clubs in the Champions League are not just United and Co. from the Big-5 leagues but dominant teams in every league. Among those winning entry to the 2013–14 tournament were clubs who made easy work of their home titles.

Celtic secured the SPL title in Scotland with four games to spare. Shakhtar Donetsk won the Ukrainian title with four games to spare. FC Copenhagen secured the Superliga title in Denmark with three games to spare. Galatasaray sealed the Turkish title after moving 10 points clear with two games remaining. Over in Amsterdam, Ajax thrashed Willem II Tilburg 5-0 to wrap up the Dutch title before the last round of games They had been on top since early March.

The only tight finish in any significant league was in Portugal, where Porto were not certain of pipping Benfica until the final day.

Whether Europe’s easy-street endings in 2012–13 were a fluke or a flexing of economic muscle should be of concern not just to the fans of clubs affected, for better or worse, but to the guardians of the game.

Sure, most leagues have one, two, or three clubs that have won a large chunk of all that league’s titles. Manchester United (20), Liverpool (18), and Arsenal (13) have won 51 of England’s 114 titles between them since 1888–89. Bayern Munich have won 23 of Germany’s 101 titles, with 22 of those titles coming in the 50 years of the Bundesliga era. Juventus (29), Milan, and Inter Milan (18 each) have won 65 of Italy’s 109 titles. Real Madrid (32) and Barcelona (22) have won 54 of Spain’s 82 titles. Rangers (54) and Celtic (44) have won 98 of Scotland’s 117 titles, with no interloper at all since Alex Ferguson’s Aberdeen in 1985. In Portugal, Turkey, and the Netherlands, powerful triumvirates have won more than half the titles.

Even against this historical backdrop, the title winners across Europe’s major leagues in 2012–13 were particularly concentrated within this group. The English title went to the “biggest” club that has also won it most often, United. The same was true in Italy (Juventus), Germany (Bayern), Denmark (Copenhagen), Turkey (Galatasaray), and the Netherlands (Ajax).

In Spain it went to one of that nation’s duo-poly clubs (Barça), as it did in Scotland (Celtic) and Portugal (Porto). In Belgium, the club with the most all-time titles, Anderlecht, won again, as was the case in Greece (Olympiacos). In Switzerland, the club with the second most all-time titles, FC Basel, won for a fourth season in a row and for the seventh time in 10 years.

Christian Seifert, the chief executive of Germany’s Bundesliga, runs a league that produced both of the Champions League finalists of 2013—Bayern and Dortmund—and can revel in acclaim for a competition that is famously populated by fan-owned clubs offering cheap tickets to exciting games in big, full, energized stadiums.

When he talks about the future of the game, it’s worth listening, and when we met in May a few days before Bayern beat Dortmund in a Wembley thriller, he told me it is time for Uefa to start working toward greater redistribution of football’s riches. “I do believe the Champions League money should be spread more evenly across all the clubs in the leagues from which the competitors come, not just those clubs,” he said. “Unless that happens, the gap in wealth will only grow more.”

His point, he stressed, was not that of redistribution will change everything or that further domestic redistribution of finances should be planned—yet. Bayern have been huge for as long as they have existed. They had revenue of $498 million in the last financial year, almost double that of Dortmund. That means, naturally, they can buy better players, pay more salary. And win more—probably.

But with one eye on this season’s results and a cautious nod to what could come, Seifert says, “If Bayern win the league the next two seasons 20 points ahead, I would say, Yes, something should change.”

.

The debut issue of Eight by Eight is available for pre-order now. Read another story from the issue here, and download a free preview here. (Cover illustration by Diego Patino). Follow Eight by Eight on Twitter: www.twitter.com/8by8mag

.

REVEALED: The best paid teams in global sport

From £200m Messi to £20m Lukaku: Europe’s 60 most valuable players this summer

Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter

POSTSCRIPT ….

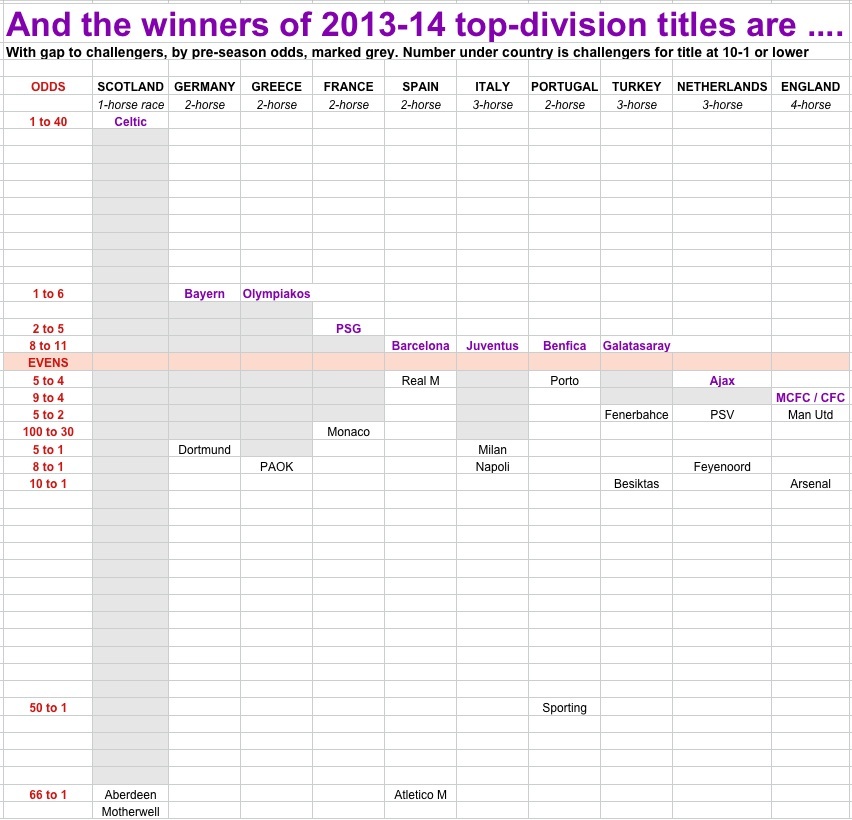

We won’t know for some months yet whether it will again be all the usual suspects winning in 2013-14. But certainly the bookmakers in early August 2013 did not expect too many contenders in each of the major title races, as the graphic below shows. And yes, there is a surprise candidate or two doing much better than expected (take a bow, Roma), but come season’s end they will be the exceptions, not the rule.