15 September 2015

Intercollegiate sports in the United States are as much a part of universities as math and physics, and the start of the 2015 NFL season is as good a time as any to explore one financial aspect of this.

Today at the elite levels of college football and basketball there are considerable tensions between big-time sports and the broader academic mission of universities. Understanding big-time athletes requires understanding that the incentives which shape big-time sport are very different than those found in college sports more generally.

A close look at last years’ NFL salary data, made possible via the Global Sports Salary Survey 2015, provides some support for different sides of the debate over college athletics. For instance, those who say that big-time college athletes should be compensated, perhaps as employees, the data shows that big-time athletics offers a considerable opportunity to secure a well-paid career. In other words, these athletes are already very well compensated in training and opportunity. Perhaps these benefits should be considered more fully?

On the other hand, for those who argue that universities offer too much attention and financial support to college athletics, the data suggests that this support results in a significant number of elite athletes, earing salaries in the millions of dollars per year. Math and physics, or any discipline, would have a hard time demonstrating such a track record of success. What is wrong with universities supporting programs that lead to hundreds of millionaires?

Let’s take a look at the data to make these contentions a bit more clear.

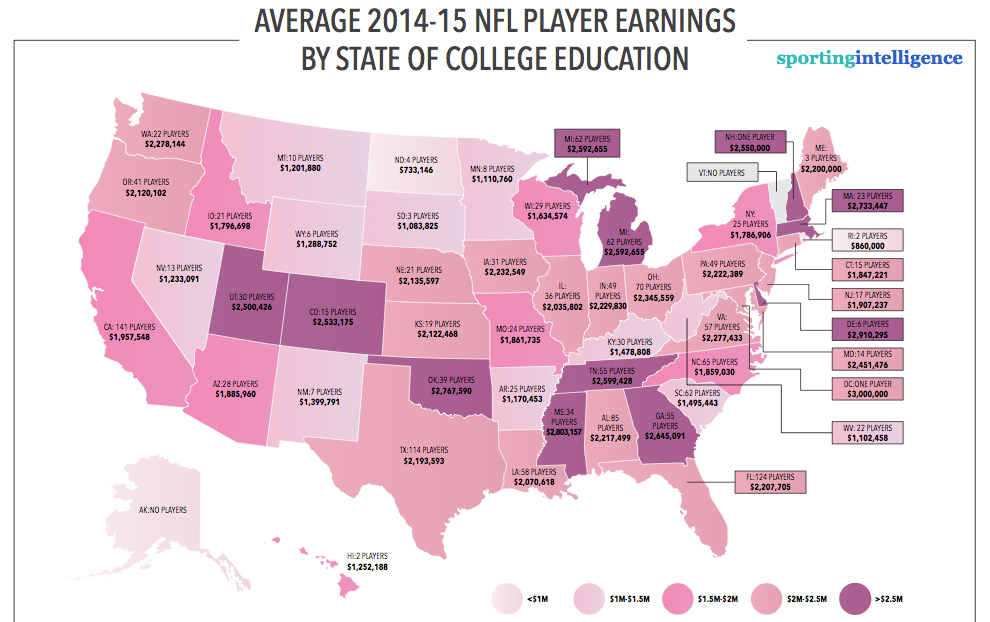

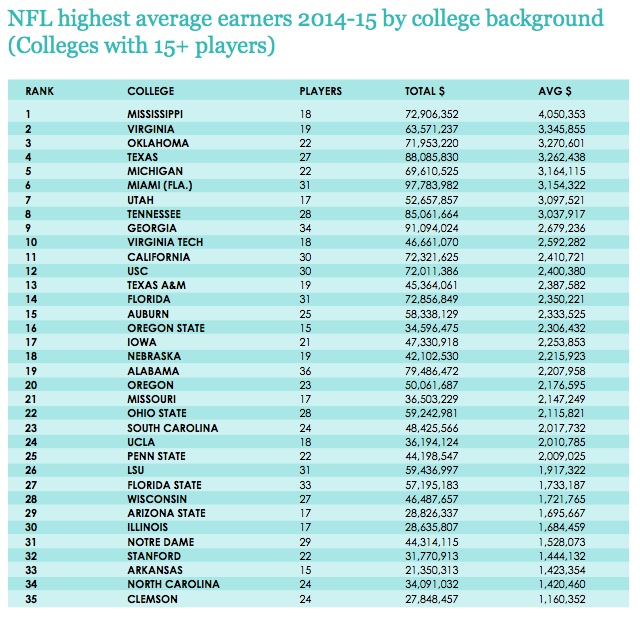

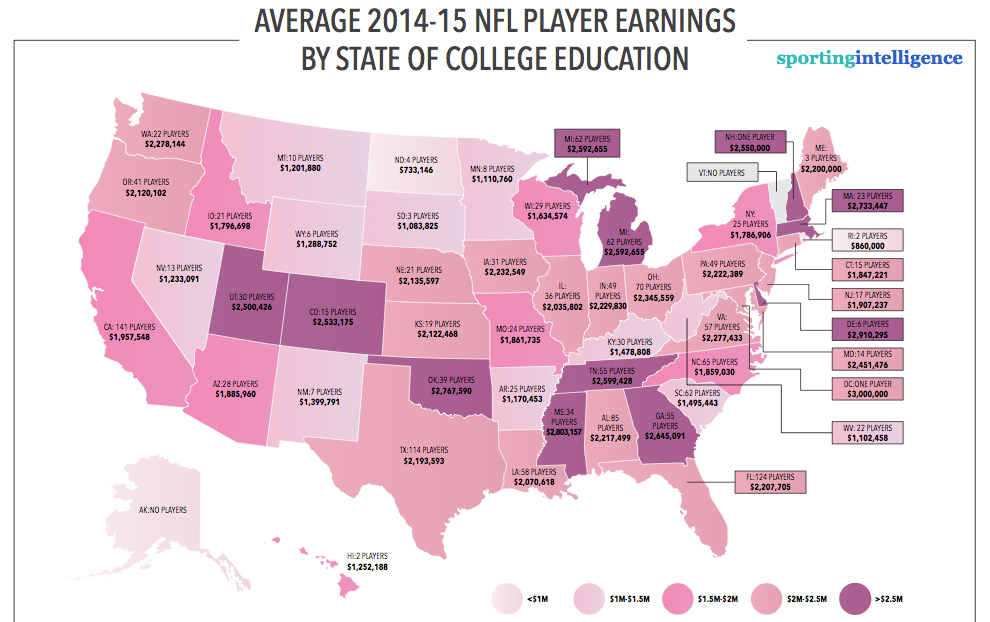

In 2014-2015 about half of the NFLs 1,600-odd players had previously played college football at 35 of the “Big 5” conferences (The Big 10, Atlantic Coast Conference, Big 12, Pac-12 and Southeastern Conference), which together total 65 schools. For instance, at the top of the average salary table is Mississippi, from the powerhouse SEC, which boasts 18 NFL players who earned an average of $4m each least season. Clemson, which sits 35th in the table, had 24 former players in the NFL earning an average of over $1.1 million each.

You can get more detail on this and the table below in the GSSS 2015.

Article continues below

If we look at just the 35 schools mentioned – what might be labelled the elite of college football – we find that for any particular individual earning a football scholarship results in a decent odds of becoming a professional player and millionaire. This is contrary to a lot of received wisdom in discussions of college athletics.

Here is the math.

Under the rules of the National Collegiate Athletics Association (NCAA) each school is allowed to award 85 scholarships for football, or 17 per season assuming 5 years of eligibility. Factoring in a conservative 10% attrition rate over those 5 years results in about 1,000 football players from the 65 schools eligible each year for the NFL draft, which selects 256 athletes each year to join professional squads.

If half of these athletes come from the 35 top schools, that implies about a 13% chance to be drafted by the NFL. If the average career length of a player that earns a roster spot is 6 years, then based on last year’s data, a football player who moved on to the NFL from one of these 35 schools over the 6 years prior to 2014 had a 14% chance of being among the 833 players from these schools (that is, 833/6,000, and note that some players earn roster spots from outside the NFL draft).

You can of course vary these assumptions to come up with different results, but one conclusion is insensitive to the assumptions, and that that the odds of a pro career are dramatically higher for athletes who play football in the elite programs than for the NCAA as a whole. The NCAA observes that in 2014, more than 71,000 college students played football, and of these, 15,800 were eligible for the NCAA draft, of which only 1.6% were drafted by the NFL.

The reality is that the odds of being drafted by the NFL and securing a roster spot with a $2 million salary are considerably higher for athletes who compete at the elite programs.

These numbers help to explain two of the dynamics of college athletics. First, universities which want to have a winning program and all that comes with it need to join the elite. Consider that there are 30 other schools among the “Big 5” power conferences that are not considered in the analysis above, and each of which has aspirations to join that exclusive club. So long as football is a deeply held American value and so long as it is played on college campuses, we will see programs strive for excellence. Universities strive for excellence in research and teaching, so we shouldn’t be surprised to see it happen in athletics as well.

A second dynamic that these numbers help to explain is the incentives for athletes to secure scholarships at the elite programs. Sure, even in these programs the odds are against any individual becoming a millionaire professional, but they are probably much higher than could be found in another other university undergraduate program. Universities routinely graduate musicians, actors, mathematicians and historians, of which a few go on to extraordinary successes, but most do not. We don’t cite those statistics to discourage participation in these fields. We do however prepare students for successful careers outside their college avocation even if they do not reach the pinnacle of their chosen profession.

The bottom line is that football, for all of its flaws and challenges, is deeply valued across the United States. For over a century it has also been a fixture of the American university. In recent decades big-time money and attention has followed college football, and this doesn’t appear to be stopping anytime soon. There are plenty of challenges facing football, among them health and equity concerns. These challenges are serious and will require a lot of effort for universities to address. Football, as well as universities, may change in profound ways.

Making football better – including safer and more integrated with universities – will require a clear understanding of the incentives that motivate programs and people. Following the money and appreciating it magnitude is a good place to start.

.

Roger Pielke Jr. is a professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado, where he also directs its Center for Science and technology Policy Research. He studies, teaches and writes about science, innovation, politics and sports. He has written for The New York Times, The Guardian, FiveThirtyEight, and The Wall Street Journal among many other places. He is thrilled to join Sportingintelligence as a regular contributor. Follow Roger on Twitter: @RogerPielkeJR and on his blog

.