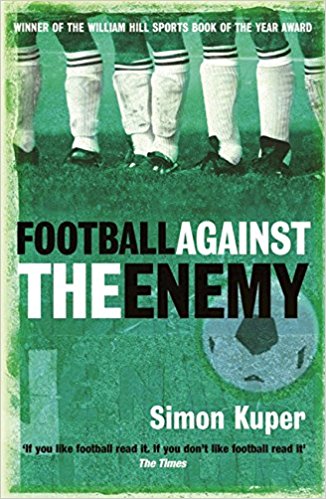

In 1994, Simon Kuper won the William Hill Sports Book of the Year award for his first title Football Against the Enemy. He visited 22 countries on a tiny budget, digging into the effects football can have on politics and culture and why different countries play the game so differently.

In 1994, Simon Kuper won the William Hill Sports Book of the Year award for his first title Football Against the Enemy. He visited 22 countries on a tiny budget, digging into the effects football can have on politics and culture and why different countries play the game so differently.

The Times said: “If you like football, read it. If you don’t like football, read it.” F.A.T.E has become a classic of sports literature. This is an extract from an interview with Kuper, part of a new 10-part podcast series, Between the Lines: The Stories Behind Great Sports Writing produced by BackPage Press

.

19 December 2017

.

Q: Does it feel like 20 years ago that the book was published?

Simon Kuper: It almost feels like a book I didn’t write it was so long ago, almost another lifetime. I finished it the night of September 5, 1993 at 2am, which was way after the publisher’s deadline. I was moving to the US to study for a year the next morning. I remember printing out all the pages and commissioning my sister to drop it off at the publishers in London, and I got on a plane to the States. It was a different world. On the table here we have the first paperback, with Frank Rijkaard and Rudi Voeller on the front and when I see that I’m jerked back in time to the young me.

Q: Where did the inspiration for the book come from?

SK: In 1990, I was listening to a radio programme about how sectarian tensions in Northern Ireland would hot up around Celtic-Rangers games. They had separate ferries getting over to Scotland to stop them beating each other up and whoever lost wasn’t happy after the game. It was a big issue for the British police in Northern Ireland, and the military. Football was an ignored topic by non-sport journalists, policy-makers, but after hearing that programme I thought ‘Wow, football can actually do things in a society.’

I had another founding experience. I grew up in Holland and supported the national team. In 1988 Holland beat Germany in the European Championship semi-final. It was the best football feeling I’d ever had in my life. Millions of Dutch folk went out into the streets, threw bicycles in the air and shouted ‘we have our bikes back!’ because the Germans had impounded Dutch bikes during the war. All the Dutch reaction from the match was about the war… and this was 1988. I realised that football could release these dormant feelings that Dutch people had against Germany.

Also being the son of an anthropologist meant I looked at football anthropologically, almost as a weird culture that needed to be studied. I loved the game but also saw it from the outside. Putting all those things together, I thought it would be great to write a book about the role of football in different countries around the world. I was 21 when the book was sold to a publisher. It was crazily ambitious. I remember staying in youth hostels in Estonia or Buenos Aires and thinking ‘this is too much, I shouldn’t have done this’.

Q: What was the reaction to the book from reviewers and readers?

SK: It came out just before the 1994 World Cup and England hadn’t qualified, so there wasn’t much for the British media to latch onto, so it got coverage, it got reviews and they were mostly positive. It was nominated for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year award. At that point I had joined the FT and they had sent me on the world’s worst journalism course in Hastings.

I said to the people who ran the course that I had to go to London for a reception in the Sportspages bookshop because my book had been shortlisted. They reluctantly let me go. I was sure it wouldn’t win but I thought I’d get a day out in London. I was standing in the bookshop and Matthew Engel was the head judge. He started saying: ‘The winning book is a fresh, young book… Football Against the Enemy’.

I went up and said to him: ‘It couldn’t have happened to a poorer man’. I was on a student journalist salary of £150 a week. Taking the bus was a stretch. I was bankrupt and suddenly I was given a cheque for £3,500, more money than I’d ever had in my life. Then I ended up in the pub with Nick Hornby and Hugh McIllvanney. Top of the world.

Q: The Cameroon chapter was fascinating. Roger Milla is an incredible character in the book…

SK: He held this tournament in Cameroon to promote the wellbeing of Cameroonian pygmies, who are very discriminated against. He brought a team of pygmies to Yaoundé, the capital, and locked them up in the stadium cellars and didn’t feed them. The pygmies were only allowed out for matches.

Milla was a slightly frustrated old man. He’d had a mediocre career in France. And as a black man in France he hadn’t been treated very well. Then aged 38 he becomes the star of the World Cup. And then his career is over. He said: “I’m like Pele, but nobody has ever paid me”, so he was slightly bitter.

To hear the full interview, subscribe to Between the Lines on your podcast app (look for the green logo). A guide for the first six episodes in the series is here.

To hear the full interview, subscribe to Between the Lines on your podcast app (look for the green logo). A guide for the first six episodes in the series is here.

.